Apple

Apple to court: Please let us help Google avoid the law

Apple asks court to halt Google search monopoly case | The Verge:

Apple writes that if its appeal isn’t handled until after the remedies trial has begun and it’s unable to participate, “Apple may well be forced to stand mute at trial, as a mere spectator, while the government pursues an extreme remedy that targets Apple by name and would prohibit any commercial arrangement between Apple and Google for a decade. This would leave Apple without the ability to defend its right to reach other arrangements with Google that could benefit millions of users and Apple’s entitlement to compensation for distributing Google search to its users.”

Translation: “Hey, Google’s been paying us $20bn in order to avoid competition and we think that’s just fine, kids. Oh and we would very much like to have similar deals in the future, so us big tech corps can keep things sewn up nice and tight. PS DONALD PLEASE HELP."

A brief history of the Finder

A brief history of the Finder – The Eclectic Light Company:

Thus, each Finder window could only show the contents of a single folder, and that location couldn’t be changed within that window. Navigating from one folder to another was accomplished by opening windows. It wasn’t uncommon to end up with stacks of half a dozen or more, each displaying the contents of a different folder, and Steve Jobs once unjustly criticised this as turning the user into a window janitor.

It’s difficult to explain to people who have grown up in the era of the GUI how advanced the Finder felt when it first appeared. As it developed, it got more complex, but the basics of how it works have come to dominate the way almost every user interface functions.

Daring Fireball: Siri Is Super Dumb and Getting Dumber

Daring Fireball: Siri Is Super Dumb and Getting Dumber:

Old Siri — which is to say pre-Apple-Intelligence Siri — does OK on this same question. On my Mac running MacOS 15.1.1, where ChatGPT integration is not yet available, Siri declined to answer the question itself and provided a list of links, search-engine-style, and the top link was to this two-page PDF listing the complete history of North Dakota’s Class A boys’ and girls’ champions, but only through 2019. Not great, but good enough.

New Siri — powered by Apple Intelligence™ with ChatGPT integration enabled — gets the answer completely but plausibly wrong, which is the worst way to get it wrong. It’s also inconsistently wrong — I tried the same question four times, and got a different answer, all of them wrong, each time. It’s a complete failure.

I’ve been saying for a while that most LLM-based “assistants” will be worse than what they replace. Older assistants were limited in domain, but largely pretty good at what they could do. LLM-powered assistants don’t know their own limitations.

The sad tale of Power Computer (and no, they weren't bought by Apple)

Most Mac users of a certain age remember Power Computing, the Mac cloner who undercut Apple with better machines back in the mid-90s. Apple ended up buying Power Computing out and putting an end to the clone market. Well if you can’t compete, use your financial muscle.

It’s often said that Apple bought the company – but it didn’t. Even Wikipedia gets this wrong, claiming that Power was an Apple subsidiary. In fact, what Apple bought was the Mac-related assets of Power, including the license to make Mac clones. Apple did not acquire the company.

And, in fact, Power had a brief life post-Apple acquisition. It attempted to launch an Intel-based Windows laptop, the PowerTrip. However, it seems to have run out of money before it could launch – at least I can’t find any references to anyone ever getting their hands on the PowerTrip – and it got sued by its suppliers.

By the end of January 1998, Power was gone. Ironically, if the company had survived for longer, the $100m in Apple stock would have been worth a lot, lot more than Power itself ever was or could have been.

I’m sure that somewhere in a box, I still have some of their stickers.

Ten Blue Links, literary salon Edition

1. Apple’s built in apps can do (almost) everything

One of the characteristics of hardcore nerdery is the tendency to over engineer your systems. People spend a lot of time creating systems, tinkering with them, making them as perfect as possible, only to abandon them a few years down the line when some new shiny hotness appears.I’m as guilty of this as the next nerd, but at least I’m aware of my addiction. It’s one of the reasons why I have spent time avoiding getting sucked into the word of Notion, because I can see myself losing days (weeks) to tinkering, all the while getting nothing done.

That said, if you are going to create an entire workflow management system and you’re in the word of Apple, you could do a lot worse than take a leaf out of Joan Westenberg’s book and use all Apple’s first party apps. They have now got to the point where they are superficially simple, but contain a lot of power underneath.

The downside is it’s an almost certain way of trapping yourself in Apple’s ecosystem for the rest of time. Yes, Apple’s services – which lie behind the apps – use standards and have the ability to export, but not all of them, and for how long?

It’s a trade off, and from my perspective not one that really works for me right now. But if it does for you, then it’s a good option (and better than Notion).

2. Juno removed from the App Store

AKA “why I do not like any company, no matter how well intentioned, to have a monopoly on software distribution for a platform.” Christian Selig created a YouTube player for the Apple Vision Pro. It doesn’t block ads or do anything which could be regarded as dubious. But Google claimed it was using its trademarks, and Apple removed it.Why is this problematic? Because it’s setting Apple up as a judge in a legal case. YouTube could, and should, have gone to a judge if it believed it had a legal case for trademark violation. That’s what judges are for. Instead, probably because it knew that it wouldn’t win a case like that, it went to Apple. Apple (rightly) doesn’t want to get involved in trademark disputes, so it shrugged and removed the app.

This extra-legal application of law is one of the most nefarious impacts of App Store monopolies. And if it continues to be allowed, it will only get worse.

3. The horrible descent of Matt Mullenweg

You will be aware of the conflict between WordPress — by which we mean Matt Mullenweg, because according to Matt he is WordPress — and WPEngine. I have many opinions on this which I will, at some point, get down to writing. The most important one is simple: if you make an open source product under the GPL, you don’t get to dictate to anyone how they use it and don’t get to attempt to punish them for not contributing “enough”. Heck, you don’t get to decide what “enough” looks like.The whole thing has brought out the worst in Mullenweg, as evidenced in his attacks on Kellie Peterson. Peterson, who is a former Automattic employee, offered to help anyone leaving WordPress find opportunities. Mullenweg decided this was attacking him, and claimed this was illegal. I don’t know about you, but when a multi-millionaire starts to throw around words like “tortuous interference” I pay attention.

As with many of that generation of California ideologists Mullenweg appears to have decided that he knows best, now and always. Yes, private equity companies that use open source projects and contribute nothing back are douchebags, but they’re douchebags who are doing something that the principles of open source explicitly allow them to do. Mullenweg’s apparent desire to be the emperor of WordPress is worrying.

4. OpenAI raises money, still isn’t a business

Ed Zitron wrote an excellent piece this week on the crazy valuation and funding round which OpenAI just closed, pointing out that (1) ChatGPT loses money on every customer, and (2) there is no way to use scale to change this: the company is going to keep losing money on every customer as models get more compute-hungry. Neither Moore’s Law nor the economies of scale which made cloud services of the past profitable are going to come riding to the rescue.I think Ed’s right — and it’s important to note, as Satya Nadella did, that LLMs are moving into the “commodity” stage — but one other thing to note is that many of the more simple things which people use LLMs for are being pushed from cloud to edge. Apple’s “Apple Intelligence” is one example of this, but Microsoft is also pushing a lot of the compute down to the device level in the ARM-based Copilot PCs.

This trend should alleviate some of the growth issues that OpenAI has, but it’s a double-edged sword because it makes it less likely that someone will need to use ChatGPT, and so even less likely to need to pay OpenAI.

5. Why I love Angela Carter

I think I first read Angela Carter during my degree, one of the few books that I bothered to read for my literature modules1. This piece includes possibly my favourite quote from her: “Okay, I write overblown, purple, self-indulgent prose. So fucking what?”And the point is: sometimes it’s fine not to be subtle. Sometimes it’s fine to be overblown. Sometimes the story demands it, like a steak needs to be juicy.

6. And speaking of writers I love

I can’t tell you enough to just go and read M John Harrison. Climbers is sometimes regarded as his best novel, and this essay on why it’s the best book written about 21st century male loneliness despite being written in 1989 captures a lot of it. I like the line from Robert Macfarlane’s introduction: “To Harrison, all life is alien”. Amen to that.7. No really this week is all lit, all the time

Olivia Laing is another writer that makes me salivate when I read her. Like Harrison and Carter, her prose is as good as her fiction, and her recent book The Garden Against Time – an account of restoring a garden to glory – is one of the best yet. If you need any further persuading, you should read this piece in the New Yorker.8. Down in Brighton? Like books?

Next weekend is the best-named literary festival in the world down in Brighton. The Coast is Queer includes loads of brilliant sessions including queer fantastical reimaginings, the incredible Julia Armfield on world building, Juno Dawson’s trans literary salon, and the unmissable David Hoyle. I’m going, you should go.9. Harlan the terrible

Like Cory Doctorow, I grew up worshipping Harlan Ellison. And like Cory, as I’ve grown older I have see that Harlan was an incredibly complicated person. Cory has written a great piece (masquerading as just one part of a linkblog) which not only looks at Harlan, warts and all, but also talks about the genesis of the story he contributed to the – finally finished! – Last Dangerous Visions.10. Argh Mozilla wai u doo this?

No Mozilla, no, online advertising does not need “improving… through product and infrastructure”. Online advertising needs to understand that surveillance-based ads were always toxic and the whole thing needs to be torn up. I agree with Jamie Zawinski: Mozilla should be “building THE reference implementation web browser, and being a jugular-snapping attack dog on standards committees.”To be clear: I think Mozilla’s goals are laudable, in the sense that at the moment the choice for people is either accept being tracked to a horrendous degree or just block almost every ad and tracker. But you can’t engineer your way around the advertising industry’s rapacious desire for data. It’s that industry which needs to change, not the technology.

- I read a lot, I just didn’t read a lot that was actually on the syllabus. ↩︎

Ten Blue Links “reinventing drink ordering” Edition

1. Inventing the future

If there is a book about Apple, I have probably read it. On my first day working at the company in 1989 I was given the obligatory copy of then-CEO John Sculley’s Odyssey: From Pepsi to Apple. After that, I devoured as much as I could.

I don’t think I have read a book like John Buck’s Inventing the Future, though. It’s getting on for 500 pages of interviews, history and anecdotes about Apple’s Advanced Technology Group, and I highly recommend it if you want to hear stories which haven’t been told before about Apple. I really wish it had an index, but it’s still well worth the money.

2. Apple’s web video mojo

Durig a conversation about Apple QuickTime, Kevin Marks pointed me at this article he wrote back in 2006 on why the company was losing its web video mojo. Kevin was right then – Apple could have owned web video – and someone really needs to sit down and write the history of that part of the company’s story. How did they mess up? As Kevin puts it “they invented pop-up web ads, and put one in before playing any web QT movie to sell the 'Pro' version of the player. They crippled the QT Player to remove the editing features unless you paid - even for the Mac users who had had the benefit before.” A lesson for today’s Apple, too.

3. Future is cleaning house

IMore, the 16 year old site which was born in the wake of the iPhone, is to close down. It’s not the only one of Future’s tech brands to be shuttered: AnandTech, the technology brand which had one of the best reputations in the world, is also going although its archive will stay online for the foreseeable future. I’m not surprised – while both sites were well regarded, they were not a great fit for the affiliate-led strategy that Future has been pursuing for many years (where it was ahead of most publishers).

4. “Pray we don’t alter the deal further”

One of the reasons I loathe – and I really do mean that – the current generation of tech giants is their ability to lock down markets for software and pull the rug out from under existing application developers. The latest example is iA, which has effectively killed off the Android version of its wonderful writing app iA Writer after Google changed the rules regarding letting applications access Google Drive. “In order to get our users full access to their Google Drive on their devices, we now needed to pass a yearly CASA (Cloud Application Security Assessment) audit. This requires hiring a third-party vendor like KPMG.” Yes, that’s right: pay an auditor maybe a couple of months of revenue in order to access cloud storage. But it’s not just Google: Apple has the same control, as iA point out in a footnote.

5. Halide rejected from the App Store

No really, it’s not just Google. After seven years, and despite being featured in the iPhone 16 keynote, an update to Halide was rejected from Apple’s App Store because its permissions prompt wasn’t explicit enough that the app, which is a camera app and takes pictures, was in fact a camera app which takes pictures. Apple admitted this was a mistake, but how many “mistakes” never get corrected because the app isn’t high profile enough to get the right level of attention?

6. Why this blog will be moving soon

I’m not a massive fan of WP Engine as a company, and I wouldn’t recommend them as a WordPress host for a bunch of small reasons, but I have no doubt at all that Matt Mullenweg’s apparent crusade against them is one of the hollowest and most disingenuous set of complaints I have seen in a long time. Pulling the rug out from users getting security updates is an unforgiveable move.

This blog is hosted by WordPress.com, and I don’t particularly want to move back to self-hosting WordPress. Anyone got any recommendations?

7. Return to work and die

I mean, literally die. For four days. With no one noticing.

8. Remember the TouchPad?

This one is a definite trip down memory lane: The HP TouchPad was a WebOS tablet that had many of the attributes necessary to compete with the iPad, and yet was dumped by HP 49 days after its release. And I had completely forgotten that Russell Brand did an advert for it. Oh boy.

9. Cosmic Alpha 2

COSMIC DE has moved into alpha 2. If you don’t know about it, it’s a new Linux desktop environment which has been created as part of the next big upgrade to PopOS, the distribution created by computer maker System76 for its range of machine. I’m using it on my ThinkPad, and – so far at least – it's been stable and very usable considering its alpha status. I’ve seen release versions of open source products be less stable. I might write something longer about my experience of Cosmic DE as I use it more.

10. Douchebros want to ruin bars, now

Sometimes I really wish that the idea of “disruption” in business had never been invented, because it really does attract some of the worst ideas. Case in point: disrupting queuing for a drink in a bar. No. Just no.

"Ireland doesn't want the money"

John Gruber on the EU ruling that Apple owes 13bn euro in taxes to Ireland:

Ireland doesn’t want the money... What a great win for Margrethe Vestager, making clear to the world that the EU is hostile to successful companies. Good job.

Ireland has long had a reputation as, effectively, an in-EU tax haven -- one which walked very close to the line of EU and international law And the country has been especially "favourable" to large tech companies. As the Irish Independent notes:

The Government continues to claim there was no special treatment for Apple, and these were all merely legitimate tax exemptions. The ECJ says otherwise, with its final judgment: “Ireland granted Apple unlawful aid, which Ireland is required to recover.” The judges ruled that Apple’s two units incorporated in Ireland enjoyed favourable tax treatment compared with resident companies taxed in Ireland that were not capable of benefiting from such advance rulings by the tax authorities here. A rotten deal, indeed.

And the Irish government itself has long known that its sweetheart deals weren't up to international standards:

As finance minister from 2017, Paschal Donohoe wisely started a process of bringing Irish rules into line – including rolling back the IP reliefs – and eventually signed up to the new OECD corporate tax deal.

Ironically -- and counter to John's point -- the conversation in Ireland is already about how to use the windfall from Apple to invest in infrastructure which will help maintain its position as a hub in the EU for tech businesses:

And then there is what Ireland can – and cannot – offer. Promises – about clean energy, top-class education, abundant water and so on – count for little now. The State has the resources to address this, helped by another €14 billion which will soon be resting in our account. But the question investors are asking is whether Ireland can actually deliver.

It's not just tax, of course. Ireland has also been recognised as the most lax data protection regime in Europe, so much so that the EDPB was forced to step in and make the Irish DPA enforce its own rules against Meta. John's reaction to that case was a little different.

Why do people get the history of Apple so wrong?

Dave Winer (who really should know better):

Graham uses Steve Jobs as an example. He knew what was and wasn't an Apple product. A hired CEO would have to have that explained to him. Sculley, who Graham cites, is a perfectly nice person in my experience, had no idea how to deal with Windows. Very different from a consumer product like fizzy waterSculley ultimately ran out of steam, but in the time he was at Apple he also took it from an $800m company to an $8bn one. Meanwhile, Jobs was back in founder mode at NeXT where, having taken some of Apple’s best people with him, he created a computer that no one wanted to buy and an operating system that remarkably few people installed.

The Steve Jobs who went back to Apple was a different person from the one that left it, chastened by the experience of business failure. It’s an interesting question of parallel history but my thought is that had Jobs won the battle and remained CEO rather than Sculley, the kind of mistakes that he made with NeXT would have probably lead to Apple suffering the same fate as most of the early computer makers who didn’t move to DOS/Windows.

Microsoft 1998 = Apple 2024

My read on this is that the EC’s stance is that its designated gatekeeping companies — all of which happen, by sheer coincidence I’m repeatedly told, to be from the US or Asia — should be forbidden from evolving their platforms to stay on top. That churn should be mandated by law.

Those of us old enough to remember back to the 1990s will recall Microsoft making very similar arguments about how antitrust was going to stifle innovation:

The Microsoft Corporation said today that a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Justice Department and several State Attorneys General is without merit and will hurt consumers and the American software industry, a leading contributor to the U.S. economy. Microsoft said it will vigorously defend the freedom of every American company to innovate and improve its products, a principle that lies at the heart of this case. Microsoft said today’s action by the Government will set a harmful precedent in which government intervention into a healthy, competitive and innovative industry will adversely impact consumers and a U.S. company’s ability to improve its products. The company said it appears that the lawsuit is more in the interest of a single Microsoft competitor than in the interest of American consumers.

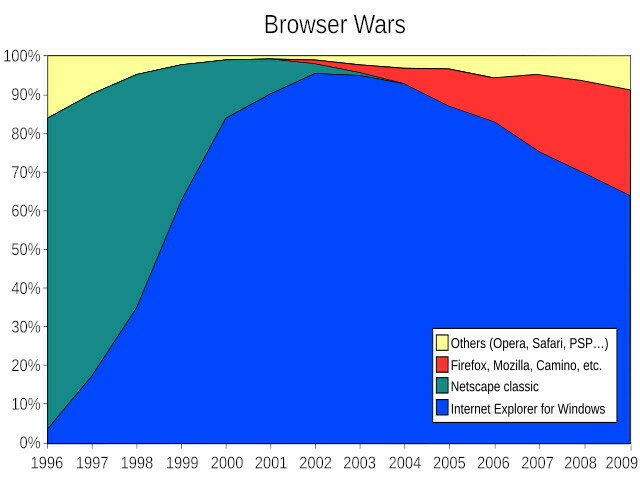

Oddly enough, when Microsoft lost its cases' innovation didn't end. What did decline after the settlement of the DOJ and EU trials was Microsoft's browser market share -- a fact which some commentators would have you believe is a complete coincidence and nothing whatever to do with governments forcing Microsoft to stop being an abusive monopolist.

Apple delays AI in the EU. Maybe.

Another day, another spat between Apple and the EU.

I'm not going to focus on the ridiculous idea that the DMA Is too vague, or that someone EU law is about "the spirit of the law" rather than its letter. You have to know nothing about EU law – or, in fact, how any law works – to believe that. Neither am I going to address the nonsensical thought that the EU is making design decisions: if you believe that regulation is "making design decisions" then both Washington and Brussels have been making design decisions in the car industry for decades.

Nor am I going to say much about the hysterical "EU IS BEING JUDGE JURY AND EXECUTIONER!!!" piffle. Just go read Article 45 of the DMA. It won't take you long, and you can read it in many languages.

What I will say, though, is that the idea that companies can't know if a feature is compliant before they release it – an idea that's well-beloved of quite a few pundits – is at best ignorant and at worst downright deception. Article 8(3) of the DMA lays out how companies can engage with the Commission to "determine whether the measures that that gatekeeper intends to implement or has implemented to ensure compliance with Articles 6 and 7 are effective in achieving the objective of the relevant obligation in the specific circumstances of the gatekeeper."

In other words, companies can engage with the EU before something is released to work out ways to stay within the DMA. The idea that it's just a crap shoot and WHO KNOWS WHAT THOSE CRAZY EUROS WILL WANT is just silly.

And maybe, in fact, that's what Apple is doing behind the scenes – in which case, it should just cut the crap and say it. Part of the mystery about this is we actually already knew some of it. Apple had already announced it wouldn't be released Apple Intelligence except in US English before the end of the year. That means, of course, EU countries weren't going to get it for a while anyway.

In the non-explanation explanation which Apple provider to John Gruber, it said this:

Specifically, we are concerned that the interoperability requirements of the DMA could force us to compromise the integrity of our products in ways that risk user privacy and data security. We are committed to collaborating with the European Commission in an attempt to find a solution that would enable us to deliver these features to our EU customers without compromising their safety.

This of course explains nothing, except stringing together “concern” with “privacy”, making ti sound like the big bad EU is going to force Apple to compromise the privacy of its users. Given the EU's long history of protecting the privacy of its citizens from US tech companies determined to operate in a wild west of personal data, this seems unlikely. And given Apple's own track record of ensuring users can't withhold their own data from Apple when it's beneficial to the company, I know who is on the side of user privacy here.

Apple is happy to cave in to even the most repressive regimes and forget about user privacy when it's beneficial to its bottom line. On the other hand, when user privacy conflicts with Apple's profits, it will go to the mat to defend its right to do what the hell it wants. That's why even if you tick the box marked "disable sharing of analytics", your iPhone will continue sharing analytics with Apple.

I really don't understand what Apple's game is here. Getting into a pissing match with a multinational block that sees the sanctity of free markets as its reason for existence and markets locked down by companies as an existential threat is not going to end well for any company.

Does it think it's going to get the DMA overturned? That a bit of magic PR will encourage a consumer rebellion of iPhone lovers riding to its rescue? I suspect it is still labouring under the impression that it's still considered “the misfits, the crazy ones”, the people who are on the side of consumers. A brand so beloved that even the EU can't touch it.

If so, I think it's become disconnected from reality. We saw with the controversy over the "crush" ad that people are now less likely to give it the benefit of the doubt, less likely to see it as the plucky underdog on the side of creative people.

For all its focus on privacy – and its genuine victories – Apple is no longer trusted in the way it was. It's begun to be considered just another big tech company, one that's prepared to throw its toys out of the pram if it doesn't get its way. When a company's value is in the trillions, it's very hard to credibly say you're on the side of ordinary people.

Some thoughts about Apple’s new iPads

Mark Gurman’s last minute “maybe an M4…” rumour turned out to be absolutely correct.

No one would have batted an eyelid had the company gone with an M3. Instead it chose to skip a generation and bring a new generation of its processors to the iPad before the Mac. The unanswered question (so far) is why?

My gut feeling is there are several drivers for this decision. First, it allows TSMC, who will be manufacturing the M4, to start with relatively small volumes. iPad’s sell well: iPad Pros, on the other hand, are a smaller part of the mix, and probably lower volumes than the MacBook Air or low-end MacBook Pros, which would have been the other option for a new chip.

Second, there is probably a performance price to be paid for that “tandem OLED” screen. Tandem OLED, by the way, is not a new thing. As reported by The Elec back in 2022, it looks like Samsung could be the manufacturer although LG Display also makes tandem OLED, mostly for the automotive market. In addition to brightness, tandem OLED gives increased lifespan and better burn-in resistance, both of which are important with a device that’s designed to be used for long periods of time.

But third is the marketing factor: by putting M4 first in the iPad, it shows that the iPad is still an important platform for the company.

One small point of note: Apple talks about M4 having “up to 10 cores”, but some models have less. The iPad Pros which have less than 1Tb of storage use a nine-core M4, and get 8Gb of RAM rather than the 16Gb of the high-end models.

This makes sense, because those iPad Pros with 1-2Tb of storage are going to be bought either to do video or because the customer has a stupid amount of money and wants “the best”. But Apple is not particularly transparent about this: go to order, and you won’t find a mention of the difference.

Of course there’s a new Apple Pencil Pro, but the second generation Apple Pencil, which a lot of current Pro owners will have, doesn’t work with it (the lower cost USB-C variant does). That means an even more expensive upgrade for existing users, who will also need to buy a new Magic Keyboard.

More importantly than the cost, Apple had a chance here to make a point that the iPad’s modular nature means you don’t have to throw away your accessories every time you upgrade. It chose not to do that, and that’s disappointing.

Another trick that Apple has missed is not improving the battery life, which remains at the usual “ten hours” or “all day battery”. And it’s not that iPad is bad on this score. But the Mac is now so much improved that it’s no longer the go-to device if you want something which is going to reduce your charging anxiety to nothing.

I’ve said it many times now, but the M2 MacBook Air has been a revelation. It turns my computer from being something where I needed to ensure I had a charger with me to a device that gets charged overnight, like my phone. For someone whose first laptop got a couple of hours that is a huge mental shift, so much so that it took me a while to racing to the nearest wall socket once I saw the battery monitor drop down to 50%.

Battery life is the biggest factor which keeps me using the Mac right now. The iPad should get the same length of use, and it just doesn’t.

The iPad Pro’s place in the universe

For a lot of us, technology is as much a hobby and a passion as a tool. We love computers because we love them as objects, not just because of what they allow us to do. I fell in love with the iPad in this way from the first day I got my hands on one, in a car park in Basingstoke where I bought a first generation one for cash from a guy who had just come back from a US trip, before they were released in the UK.

Apple often talks in a way which makes my marketing-cynical eyes roll, but its description of the iPad as a “magical sheet of glass” is, to me, real. A computer that’s just a piece of glass, that you can use as a slate when you want, as a creative powerhouse, as a book, as a TV, and that is capable of transforming its physical form by use of accessories to do all those things well – that’s something amazing.

The iPad should be that one device but somehow, 14 years down the line, it’s still not. My gut feeling is this comes down to the restrictions which Apple continues to place on what developers (and customers!) can do with it compared to the Mac or any real computer. All of the arguments people make about customer benefits to a locked-down ecosystem don’t apply to a computer which is designed to be your main device.

About that ad

I don’t think I have ever known Apple apologise for an ad before. It has quietly withdrawn them (including the What’s a computer? iPad ad, which I liked but you won’t find now on an Apple channel), and it has had duffers that it would rather people didn’t remember.

Like John Gruber, I didn’t really think it was that bad on first viewing, although it did strike me as pretty tone deaf. It definitely didn’t get the message across, which was that the iPad can be all these wonderful creative things. Instead, it focused on the destruction of creative things, which isn’t “at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts” at all.

But thinking about it more, Apple should have predicted the reaction to it. It isn’t the plucky underdog anymore: it’s one of the biggest technology companies in the world, and people are (justifiably in my view) wary of it because of that. Where perhaps 10 years ago people would take its environmental claims at face value and believe it’s control freakery was down to a desire to deliver the best experience for customers, now less people want to give it the benefit of the doubt.

Including, of course, me.

On the iPad becoming a Mac

Jason Snell wants the iPad to be able to be a Mac:

The iPad no longer feels like the future of computing, and that’s fine. The Mac is here to stay, something that didn’t seem like a sure thing five and a half years ago. It feels like it’s time for Apple to accept this state of affairs. macOS isn’t just one of Apple’s platforms—it’s a feature, a secret weapon that it can use to make all its other platforms more powerful when they need to be.

I don’t have any idea if Apple really has any intention of letting macOS run on other devices, whether it’s an iPad or a Vision Pro or even an iPhone plugged into an external display. But it seems to me that if there’s any Apple product that is flexible enough to make it work, it’s the iPad Pro.

I was a big iPad Pro user for quite a while, and a proponent of its simplified but powerful operating system. There are plenty of apps on the iPad which are brilliant, and developers have done a lot with the platform.

Since I got an M2 MacBook Air, though, my use of the iPad Pro has fallen away almost to nothing. While Apple has long billed the iPad Pro as its most versatile computer, capable of being a tablet, a laptop, or whatever, when it comes to the most important thing of all – software – the iPad isn't versatile enough.

I can't install another browser which uses a different rendering engine. All browser plugins have to be installed via an app store. I can't get software of any kind from anywhere except an app store. Although the file system has improved, it's still limited compared to that of a more open platform like the Mac.

And of course, if I ever decided I wanted to take my expensive piece of hardware and install a completely different operating system on it, well… tough.

When people talk about wanting the iPad to be a Mac, what they're ultimately saying is they want the platform to be more open because all of the decisions that Apple has made which lead to it being inferior to the Mac are about keeping it more closed. And I'm going to hazard a guess, given the way Apple has had to be dragged through a legal process just to open up a little, that's not on the company's agenda.

But I would love to be proved wrong.

Did IQs drop sharply while I was away?

AppleInsider: –"EU's antitrust head is ignoring Spotify's dominance and wants to punish Apple instead":

Speaking to CNBC the EU's Margrethe Vestager said her office was continuing to investigate Spotify's complaint that it is being prevented from reaching its audience. Spotify is currently the leading music streaming service in the world, while Apple Music is variously in fourth or fifth place.

Repeat after me: Spotify is not a gatekeeper. Apple is. Special rules apply to gatekeepers to stop them using their market power in one area to distort a free market in another.

This is not rocket science, and I'm at the point where I think if a journalist is getting it wrong, they're simply propagandising for Apple, Meta, or Google.

What a difference four years makes

John Gruber in 2020 on the tracking industry led by Facebook:

The entitlement of these fuckers is just off the charts. They have zero right, none, to the tracking they’ve been getting away with. We, as a society, have implicitly accepted it because we never really noticed it. You, the user, have no way of seeing it happen. Our brains are naturally attuned to detect and viscerally reject, with outrage and alarm, real-world intrusions into our privacy. Real-world marketers could never get away with tracking us like online marketers do… Just because there is now a multi-billion-dollar industry based on the abject betrayal of our privacy doesn’t mean the sociopaths who built it have any right whatsoever to continue getting away with it. They talk in circles but their argument boils down to entitlement: they think our privacy is theirs for the taking because they’ve been getting away with taking it without our knowledge, and it is valuable. No action Apple can take against the tracking industry is too strong.

John Gruber in 2024, on the EU's actions which limit Facebook's ability to track users:

What makes this all the more outrageous is that many major publishers in the EU use this exact same “pay or OK” model to achieve GDPR compliance — and none offer a free alternative with non-targeted ads. Don’t hold your breath waiting for Der Spiegel to offer free access without ads. Christ, they don’t even let you look at their homepage without paying or consenting to targeted ads. And Spotify quite literally brags about its ad targeting. But Spotify is an EU company, so of course it wasn’t designated as a “gatekeeper” by the protection racketeers running the European Commission… They’re not saying “pay or OK” is illegal. They’re saying it’s illegal only if you’re a big company from outside the EU with a very popular platform.

I wonder what happened to turn John's attitude from “no action Apple can take against the tracking industry is too strong” to defending Facebook's “right” to choose how it invades people's privacy? Or is he suggesting that a private company is entitled to defend people's privacy, but governments are not?

And John's second point about Spotify fundamentally misunderstands the nature of antitrust law in general and the EU gatekeeper system specifically. In competition, actions which are legal when you're not a monopoly become illegal when you are a monopoly.

In particular, Apple – and Facebook – are gatekeepers because they “are digital platforms that provide an important gateway between business users and consumers – whose position can grant them the power to act as a private rule maker, and thus creating a bottleneck in the digital economy”. Spotify is not in that position. Der Spiegel is not in that position. Different rules apply – as they do to Tidal (not an EU company), and of course to the New York Times.

This really is not difficult to understand.

But underneath this in part is John's feeling that EU antitrust law is all an EU conspiracy to attack American companies. That would be news to Daimler, fined over a billion euros for an illegal cartel. It would news to Scania, fined 880m euro. To DAF, fined 715m euro. To Phillips, fined 705m euro. And so on. The EU fines European companies big sums of money all the time for breaking competition law.

The entire point of the EU is to create single, competitive markets. It does not allow big companies to “own” markets because free markets (in the EU's eyes) are good, and privately owned ones that allow big companies to stop being capitalists and act like feudal lords are bad. Facebook, Apple, and the rest have been doing this in digital for a long time, and the EU has decided it's going to stop.

Antitrust, Meta, Apple and more

John Gruber: More on the EU’s Market Might:

If they follow through with a demand that Photos be completely un-installable (not just hidable from the Home Screen, as it is now), this would constitute another way that the EC is standing in as the designer of how operating systems should work.

A lot of commentators seem to have the same issue as John: that it’s weird that a governmental body can or should define how products should be designed.

But governments mandate how products are designed all the time, and not just in the EU. Take another market which is pretty big: cars. All cars have to feature safety equipment, which varies from region to region but will broadly include everything from seatbelts to crumple zones. Cars have rules for emissions, for fuel efficiency, all of which are designing how a car should work.

John then kind of hits the nail on the head:

Why stop there? Why not mandate that Springboard — the Home Screen — be a replaceable component? Or the entire OS itself? Why are iPhone users required to use iOS?

To which the obvious answer is why indeed?

I paid Apple £1099 for my last iPhone. It made a handsome profit on it, probably between 30-40%. At that point, Apple should no longer be able to stop me from doing what the hell I want with the product I purchased. So yes, the fact that it does exactly that is problematic.

Apple doesn’t do that on the Mac I’m typing on. Why should it have that level of control over the iPhone I bought?

And yes, I know the “well you bought an iPhone and you knew that was part of the deal ha ha” argument. That argument is weak, because people's needs evolve and what people want evolve. Maybe now I'm super-happy with the way that Springboard works. And perhaps in a year's time Apple will introduce a new version, which sucks. But I won't be able to replace it with a third party alternative, despite the phone being a year old, despite it being perfectly good.

Because, of course, I don't own my phone, despite that money I paid for it, despite that margin Apple got.

The EU isn't just concerned with today. It's really taking Steve Jobs’ advice and listening to the Wayne Gretzky quote: it’s skating to where the puck is going, not where it’s been. Its aim is to ensure that two very large companies don’t own the market for smartphones to such a degree they can determine everything that happens in those markets, to their advantage. The EU is a capitalist body: its obsession is keeping markets open, and it will do anything it needs to do to make sure that happens. They can act now, or they can act later when the adjustments required – both for big companies, third parties and consumers – would be far greater.

The obvious solution would be for the European Commission to pass a law banning targeted advertising. But I suspect they haven’t done that, and won’t, because so many publishers in the EU use targeted advertising (along with “pay or OK” subscription offerings). They don’t want to eliminate all targeted advertising, just Meta’s (and Google’s), but that’s hard to put into written law while claiming not to be targeting very specific American companies.

The EU prefers not to ban products outright. Remember, it’s a capitalist body. It loves markets! But it’s not like it hasn’t pushed targeted advertising hard to try and get the balance between a useful product and people's privacy. Laws affecting it include:

- the ePrivacy Directive (Directive 2002/58/ED).

- a little thing called the GDPR (Regulation (EU) 2016. You may have heard of it.

- the eCommerce Directive (Directive 2000/31/EC).

- the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (Directive 2005/29/EC).

- the Directive on Misleading and Comparative Advertising (Directive 2006/114/EC).

- the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/1808).

- the Consumer Rights Directive (Directive 2011/83/EU).

It’s not like the EU hasn’t investigated targeted advertising, and (unfortunately in my view) the issue isn’t targeting in itself but the ways Meta (and separately Google) have been implementing it. This is the point that John highlights Thierry Breton making:

But the DMA is very clear: gatekeepers must obtain users’ consent to use their personal data across different services. And this consent must be free! We have serious doubts that this consent is really free when you are confronted with a binary choice. With the DMA, users who do not consent should be provided with a less personalised alternative of the service, for example financed thanks to contextual advertising. But they do not have to pay.

The EU told Meta explicitly that its contract with users was a problem. Rather than change the contract substantially to stop violating the law, it chose to offer a different contract for paying customers. The point isn’t that a paying option is or is not popular: it’s that Meta has tried to evade what the courts have explicitly told them to do.

As American companies are learning, the EU does not like companies that try and do an end run around the law. This appears to have dawned on Apple, which has already – in the space of a few weeks! – widened its plans to comply with the DMA and DSA. Perhaps not enough, which is why the EU is investigating them. But the mood from Apple has definitely started to change from sullen evasiveness to being more open to compliance. It's not yet at the point of working to make a good compliant product for its customers, but it's getting there.

One other point of course: Breton’s comments are demanding that Meta implement a system in a way similar to that which Apple forced them to do on iOS. App Tracking Transparency made Meta, and all other app makers, ask if the app could track them – and Apple didn’t give a damn that it would cost Meta $10bn. Apple also wouldn’t have accepted an opt-out where Meta charged you if you opted out of ATT. John’s argument seems to be that it’s fine for Apple to do things to protect the privacy of its customers, but it’s not OK for the EU to do the same for everyone.

Consider too that if Meta goes along with this interpretation by the EC of the DMA’s requirements, and offers a vastly-less-lucrative free-of-charge option to use Instagram and Facebook without targeted ads in the European Union, there’s nothing to stop regulators and legislators around the world from demanding the same. Conceding to this might mean not just generating only a fraction of Meta’s current revenue in the EU, but generating only a fraction of its current revenue worldwide.

To which I can imagine Breton giving something of a gallic shrug. Because, again, the point of the EU – its very purpose – is to ensure that markets are free and open. The idea that a single company should determine what markets can and cannot be open is an existential threat to the EU.

Breton — after casting a stink eye at Google for presenting its own hotel, flight, and shopping recommendations in web search results, and at Amazon for promoting its own Amazon-branded products (a shocking practice for a retailer — good luck ever finding Kirkland products at Costco, Up & Up at Target, or, say, Ol’ Roy dog food at Walmart, right?)…

Let’s just pause at this point and remind ourselves that Google has 91.62% of the search engine market, and repeat – again – that the rules of what you can and can’t do as a business change when you have a dominant market position.

(Aside: the FTC and other antitrust bodies are, in fact, casting their eyes on the likes of Walmart too. And in Europe, many retailers and non-tech companies have fallen foul of antitrust rules. It’s not just about tech.)

On to our scheduled programming:

Turns out, though, that actual users don’t agree that removing longstanding features from Google search results is somehow for their benefit. I’m guessing they’d see even less benefit if entire popular services and products are removed from the EU market.

Leaving aside that John is linking as “proof” to a Reddit thread with precisely nine comments on it, most of which are from US users and none of which sound particularly outraged, this misses the point of antitrust action entirely, doubly so in the EU. So, for what feels like the 900th time, I’ll explain it:

The point of antitrust action is to ensure that markets remain competitive, because over time competition spurs innovation and ensures prices are optimal.

That’s it. That’s all. It’s not about immediate prices – although over time, competition lowers them. It’s not about “making customers happy” – although, over time, competition leads to happier customers, because it spurs innovation.

It’s understandable that people with a American view of antitrust based on recent history might not get this. The focus in US antitrust since the early 1980s has been on prices, thanks to the noxious influence of Robert Bork. In Borkian antitrust, all that mattered was prices, and, in his weird head, monopolies led to lower prices for consumers. That this went against pretty much every economic theory since (and including) Adam Smith didn’t matter.

Thankfully US antitrust bodies appear to have cottoned on to how bizarre Bork’s approach was and are abandoning it. But if you haven’t been paying attention to antitrust history and have grown up since Reagan, you probably don’t understand the change.

In a footnote, John notes this:

One obvious solution would be to show more ads — a lot more ads — to make up for the difference in revenue. So if contextual ads generate, say, one-tenth the revenue as targeted ads, Meta could show 10 times as many ads to users who opt out of targeting. I don’t think 10× is an outlandish multiplier there — given how remarkably profitable Meta’s advertising business is, it might even need to be higher than that. But showing that many ads would be such a bad experience that I suspect it would land Meta right back where they are today with the paid subscription option, with the EC declaring it non-compliant because users don’t want it.

And here’s the thing: that’s fine. It’s fine because, instead of having a business model reliant on invading people’s privacy, largely without their consent or even any kind of transparency, Meta would be forced to compete without doing those things. It would be forced to make a product which respected people as people, instead of exploiting its undoubted market power.

I am totally fine with that.

Maybe 10 ads would be enough to maintain its current level of profits. And maybe that would make users unhappy. And maybe then another company would come along and offer a similar service with five ads, and people could choose to use it because it’s a better experience.

And that might push Facebook to make its service more efficient, or lower its margins, so it could offer five ads too. Perhaps it could charge a higher price for them because it found technical ways to do better targeting while staying within the bounds of the law. Or maybe Facebook would die and be replaced by something else, just as MySpace, FriendFeed, and all those other early services fell by the way side because they weren’t as good an experience as Facebook.

That’s how competition works. Not by lock-ins, tying, bundling, “walled gardens” (that you can’t easily leave). All of those things are symptoms of a market out of control. The EU, which up till now has mostly confined itself to measures like GDPR which just ameliorate the symptoms, has decided it’s going to try curing the disease itself.

A few thoughts on the Apple DOJ antitrust case, from someone who isn't riding his first rodeo

From 1995 through to about 2008, I made my living from technology journalism (we called it “computer journalism” then, because technology really was computer). That means my career almost exactly spans the period of the biggest technology antitrust trials of the lot: United States vs Microsoft, and Microsoft vs European Commission. Most of the original reporting I did was about the EC case (after all, that's my side of the pond) but I did enough reporting and spoke to enough sources to have a decent idea of the nuances of both cases.

Depending on how you look at it, US vs Microsoft (which I'll call “the DOJ case”) was either the last hurrah for a DOJ which had become very reluctant to intervene in anything connected with antitrust that wasn't either a cartel or big merger, or the first case where network effects were regarded as an important question in competition law. But either way, it was one of the landmark cases in technology competition law, as notable as the breakup of 'Ma Bell' or the 1956 IBM consent decree.

So, based on my specific expertise, I can tell you: Be prepared, over the coming months, for some lousy punditry.

Tech commentators (and their audiences) are going to have to learn some history

An entire generation of tech commentators and CEOs have grown up not understanding the history of antitrust in tech, or the impact it had in shaping the industry. And they really don’t understand that without regulatory action in the 1950s to 1980s, their businesses would not exist.

One simple example: why did IBM not buy DOS outright, a move which would have killed the PC compatible before birth and made IBM dominate for longer? Bill Gates would love everyone to think it’s because he was smart and IBM was not. In fact, it’s because IBM was wary of yet another antitrust suit. As Bill Lowe put it, “IBM didn’t want to be seen as dominating the market too thoroughly.”

Similarly, IBM could have bought Microsoft — Gates even offered them 10% of the business, and they could easily have afforded more. In the environment of the past 20 years, where big companies are allowed to buy almost anyone, they would have. Back then, antitrust concerns made it a non-starter.

And now antitrust law is being applied again in the way it has been for most of its existence, commentators and tech execs are finding it really difficult to cope with the change. There’s an irony that Tim Cook appears to be affected deeply. After all, Cook started his career at IBM, and moved on to Compaq - a company that wouldn’t have existed without antitrust law. You would think he would get it.

If you would like to know more about the impact of antitrust on IBM behaviour, I’d recommend reading this paper by Tim Wu. In his conclusions, he looks at what antitrust regulators should learn from the case, and I found this paragraph quite relevant to what’s currently happening:

A similar logic suggests prioritizing Sherman 2 cases where the problem isn’t just competition in the primary market, but where competition in adjacent markets looks to be compromised or threatened. The long cycles of industrial history suggest that what are at one point seen as adjacent or side industries can sometimes emerge to become of primary importance, as in the example of software and hardware. Hence, the manner of how something is sold can make a big difference. In particular, “bundling” or “tying” one product to another can stunt the development of an underlying industry. Even a tie that seems like “one product” at the time the case is litigated, as, for example, software and hardware were in the 1960s, or physical telephones and telephone lines, might contribute to such stunting. If successful, an antitrust prosecution that breaks the tie and opens a long-dominated market to competition may serve to have very significant long-term effects

Expect lots of talk about how previous antitrust action (in particular Microsoft) didn't achieve anything

Views I have heard in the past few years from some widely known pundits:

- Microsoft/DOJ did nothing to change the browser landscape

- Microsoft/DOJ didn't make any difference to Microsoft's ability to “win” in mobile

- Microsoft/DOJ didn't matter because the web

To borrow a phrase from Ben Thompson, these opinions are, to use a technical term favoured by analysts, bullshit. All of them have in common a failure to understand the chilling effects that being under investigation, or under a consent decree, have on corporate actions –– at every level.

In organisations that are under antitrust pressure, ideas that might get put forward are held back, because people would rather not spend the time having them checked through legal and compliance teams. Acquisitions which a company might make don't happen, because it would rather not appear rapacious or that it's stifling nascent competition. And contractual clauses with partners can't be as aggressive in locking them out of doing business in a way which doesn't favour you. That, of course, was one of Microsoft's favourite tricks of the 1990s: the “per processor” licence for Windows, for example, meant that computer makers paid them for a licence on every computer, whether Windows was installed or not.

Microsoft tried to tie Internet Explorer to Windows. It was stopped from doing so by the government, and that made it a lot easier for Chrome to gain traction. As Gates said (and Thompson denies!) the “distraction” of antitrust meant that Microsoft wasn't as focused on mobile as it should have been. The “old” Microsoft would also have used specific means to stop the iPhone being as attractive, such as preventing it from connecting to Exchange servers (something that was introduced in iOS 2, in 2008).

Antitrust action works, in part, not just because of the explicit conditions of a consent decree, but because companies limit themselves. They are afraid of getting back into court, because they know that next time a break-up might be on the agenda.

Expect to see a lot of bad commentary because people don't understand “monopoly power” or market definitions

I have already seen a lot of “the iPhone is not a monopoly!” comments, from people who have been in the business for long enough to know better. Let's put that one to bed straight away: “monopoly power” does not require a literal monopoly share of a market. Here's how the FTC defines it:

Courts do not require a literal monopoly before applying rules for single firm conduct; that term is used as shorthand for a firm with significant and durable market power — that is, the long-term ability to raise price or exclude competitors. That is how that term is used here: a “monopolist” is a firm with significant and durable market power. Courts look at the firm's market share, but typically do not find monopoly power if the firm (or a group of firms acting in concert) has less than 50 percent of the sales of a particular product or service within a certain geographic area. Some courts have required much higher percentages. In addition, that leading position must be sustainable over time: if competitive forces or the entry of new firms could discipline the conduct of the leading firm, courts are unlikely to find that the firm has lasting market power.

This is why the DOJ filing talks about “monopoly power” and how Apple “also enjoys substantial and durable market share”:

Apple has monopoly power in the smartphone and performance smartphone markets because it has the power to control prices or exclude competition in each of them. Apple also enjoys substantial and durable market shares in these markets.

Note the “also”. The DOJ case does not rely on a specific high number for Apple market share: it relies on showing that Apple has significant market power.

But one of the key elements in any antitrust case is the definition of the markets you're referring to -- because defining the market helps understand the degree to which a company has monopoly power. The DOJ filing talks about two markets, hence the title of section E: “Apple has monopoly power in the smartphone and performance smartphone markets”

The DOJ claims that Apple itself says it has a 70% market share in the second one:

In the U.S. market for performance smartphones, where Apple views itself as competing, Apple estimates its market share exceeds 70 percent

I can't locate a source for Apple saying this, but I have no doubt at all that the DOJ can back up both the number, the market definition, and that Apple has said -- publicly or internally -- that it is the market it competes in. Market definitions are so important to antitrust cases that the DOJ just would not have included that statement without evidence to back it up.

(And no, Apple, you can't play it like the market share that's relevant is the global number. You're not going to appear in the Global Court of Justice, it's a United States one – and they tend to only care about what's going on in the US.)

Don't believe anyone who says the DOJ complaint is badly written, unless they are an actual legal expert

Exhibit one, Benedict Evans:

“It still amazes me how sloppy this DoJ filing is. It's Apple's fault that LG and HTC could not compete with Xiaomi, Oppo and Samsung? Google Android phones are outsold by Samsung Android phones… because of iMessage? WTF? Ther's [sic] stuff like this on every page. How did this get out of a drafting session? Everyone at the DoJ should be professionally embarrassed.”

Exhibit two, Rebecca Haw Allensworth, antitrust professor and associate dean for research at Vanderbilt Law School:

“They told a very coherent story about how Apple is making its product, the iPhone and the products on it – the apps — less useful for consumers in the name of maintaining their dominance… This is just a more plausible story about consumers, [making it] as a legal matter, a stronger lawsuit.”

Well, I just don't know who to believe here – what do you think?

Ten Blue Links, AI is bad now edition

First up, apologies that there's been no long form post this week. I've had some family stuff which had to take priority over writing. Normal service should be resumed from next week.

And now on to the good stuff…

1. The last refuge of the desperate media

Ahh, low rent native ads — the kind that are designed to fool people into clicking by appearing to be genuine user or editorial posts. Always a sign that a company is desperate for revenue, any kind of revenue, and never mind the longer-term implications on quality. Now, why would Reddit want to do that?

2. Repeat after me: AI is not a thing

More specifically, AI is not a single technology, and what we talk about in the media as “AI” is, in fact, quite a limited, relatively new tool coming out of AI research — the Large Language Model, or LLM. Why does this matter? Because (how shall I put this?) less technically educated executives are likely to read articles like this one, about the successful use of AI in the oil industry, and think that they need to jump on the AI bandwagon by adopting LLMs. These are two very different things: Robowell, for example, is a machine learning system designed to automate specific tasks. It learns to do better as it goes along — something that LLMs don't do.

3. Tesla bubble go pop

The notion that Tesla was worth more than the rest of the auto industry combined was always bubble insanity, and it looks like the Tesla bubble is finally bursting. And this, of course, is why Musk is grabbing on to AI and why he proposed OpenAI merge into Tesla: AI is the current marker for a stock to end up priced based on an imaginary future rather than its current performance. Musk needs to inflate Tesla again, and just being an EV maker won’t now do that.

4. This is fine

I'm almost boring myself now whenever I post anything about the era of mass search traffic for publishers drawing to a close. But then someone comes up with a new piece of researching showing an impact of between 25-60% traffic loss because of Google's forthcoming Search Generative Experience. The fact that Google effectively does not allow publishers to opt out of SGE — you have to opt out of Googlebot completely to do so — should be an indication that Google has no intention of following the likes of OpenAI in paying to license publisher content, too. And I think the SGE is just the first part of a one-two punch to publisher guts: computers and how we access information is going to become more conversational and less focused on searching and going to web pages. As that happens, the entire industry will change, and it could happen faster than we think.

5. Feudal security

I often link to Cory Doctorow's posts, and it's not just because he's a friend -- it's because a lot of the things that he's been talking about for years are beginning to be a lot more obvious, even to stick-in-the-muds like me. This piece starts with a concept that I have struggled to articulate -- feudal security — and sprints on from there.

6. LLMs are terrible writers

Will Pooley has written a terrific piece from the perspective of an academic on why LLMs just don't write in a way which sounds human. They don't interrogate or question terms (because they have no concepts, so can't), there is no individual voice, they make no daring or original claims based on the evidence, and much more. My particular favourite — and one I have encountered a lot — is that LLMs love heavy sectionisation and simple adore bullet points. I've got LLMs to write stuff before, specifically telling them not to use bullet points, and they have used them anyway. As Tim succinctly put it in a post on Bluesky, LLMs create content which is “uniformly terrible, and terribly uniform”.

7. Craig Wright is not Satoshi Nakamoto

Craig Wright spent a lot of time claiming he was the pseudonymous creator of Bitcoin, and suing people on that basis. Finally, a court has ruled that he was lying. Whoever Nakamoto is/was, he's probably on an island somewhere drinking a piña colada.

8. Google updates, manually hits AI-generated sites

You might have noticed that Google did a big update in early March, finally responding to what everyone had been saying — that search had become dominated by rubbish for many search terms. Smarter people than me are still analysing the impact of that update, but one thing which stood out for me is there was a big chunk of manual actions to start. Manual actions are, as the name suggests, based on human review of a site, which means they are a kind of fallback when the algorithm isn't getting it right. And guess what the manual actions mostly targeted? AI content spam. All the sites that were whacked had some AI-generated content, and half of them were 90-100% created by AI. Of course, manual action is not a sustainable strategy to combat AI grey goo, but it should be a reminder to publishers that high levels of AI-generated content are not the promised land of cheap good content without those pesky writers. If you want to use it, do it properly.

9. The web is 35 years old, and Tim Berners-Lee is not thrilled

The web was meant to be a decentralised system. Instead, it's led to the kind of concentration of power and control that would have made the oligarchs of the past blush. That's just the starting point of Tim Berners-Lee's article marking the web's 35th anniversary, and he goes on to provide many good suggestions. I don't know if they are radical enough — but they are in the right direction.

10. A big tech diet

It's a long-standing journalistic cliché to try some kind of fad diet for a short period of time and write up the (usually hilarious) results, but in this "diet" Shubham Agarwal tried to drop products from big tech companies, and of course, it proved harder than you would think. Some things are pretty easy — swapping Gmail for Proton isn't hard (and Shubham missed out some tricks, like using forwards to redirect mail). But it's really difficult to avoid some products, like WhatsApp or LinkedIn, because there are few/no viable alternatives. That, of course, is just how the big tech companies like it because they long-ago gave up on the Steve Jobs mantra of making great products that people wanted to buy in favour of making mediocre products that people have no alternative to using.

Michael Tsai - iOS 17.4 Changes PWAs to Shortcuts in EU

Michael Tsai - Blog - iOS 17.4 Changes PWAs to Shortcuts in EU:

Apple had two years or so to prepare for the DMA, but they “had to” to remove the feature entirely (and throw away user data) rather than give the third-party API parity with what Safari can do. I find the privacy argument totally unconvincing because the alternative they chose is to put all the sites in the same browser. If you’re concerned about buggy data isolation or permissions, isn’t this even worse?

Michael neatly collects together the responses to Apple’s frankly pathetic removal of proper PWA support in the EU, but I think his own quote above hits the nail on the head. The company has had years to prepare for this. If it got blindsided, that’s a management failure. If it’s being petulant, that’s a management failure. If it can’t devote the resources to make this work, that’s a management failure. And if this is an attempt to enforce using native APIs and the App Store rather than PWAs… well, that too is a management failure.

Apple’s whole response to the DMA ruling has been nothing but disastrous for its credibility amongst developers, but unfortunately the company seems to have forgotten that without developers, its platforms are nothing but pretty user interfaces for copying files around.

Daring Fireball: The European Commission Had Nothing to Do With Apple’s Reversal on Supporting RCS

Daring Fireball: The European Commission Had Nothing to Do With Apple’s Reversal on Supporting RCS:

China, unlike the EU, seemingly knows how to draft effective regulations to achieve specific goals.

China, unlike the EU, is a repressive regime with a chokehold over Apple’s business. I don’t think Apple caving in to it has much to do with the quality of how China drafts its laws.

Some thoughts on Apple Vision Pro (and VR/AR in general)

- As many people have noted, the ultimate platform for augmented reality is something that is both portable (can be worn all the time) and invisible (not a huge set of goggles which get in the way of your interactions with the world. We are so far away from this in terms of technology that I would be surprised if we even have it in my lifetime (see also: fully autonomous vehicles that you can drive in).

- The price of Apple Vision is not unreasonable given the technology in it. They are not selling this at a loss, and I would expect the margins on it are similar to other Apple products, but Apple Vision is not something that can currently be made at under $1000, which is probably the sweet spot for this kind of tech.

- As with the Apple Watch, the company has a set of use cases in mind. As with the Apple Watch, these will almost certainly not be the uses that customers actually find most compelling. Expect the marketing to shift in response to what actually resonates with people.

- This represents a minor potential issue for Apple. Apple Watch was priced low enough to have quite a wide spread of customers, especially once the cheaper hardware options appeared after a year or two. Apple Vision is priced too high to get a wide range of customer types. The danger is that it will skew too heavily towards highly-affluent customers, and they kinds of uses they make of devices, for Apple to get much insight into what the real uses of Apple Vision are. Apple doesn’t do much testing with real users (even under NDA) before products are released. That means real-world feedback is vital.

- The criticisms that people have made about the battery life are really not that relevant. No one is going to use this wandering around. You’re going to mostly have your behind in a chair. I’ve done a lot of VR demos when moving and nothing breaks the “reality” of the app you’re using than trying to do much in the physical world. Yes, the passthrough video means you can do this. But trust me, you won’t.

- It’s a shame that you can’t have multiple Mac “monitors” open at the same time. But you can have multiple apps, so I would guess quite a few of the things you want to keep open on multiple monitors will devolve to native apps.

- It’s a bigger shame Apple has chosen to only have an App Store model for software. The lack of hackability of the platform won’t matter to most people, but it does matter to me. This isn’t a market of customers who need the same level of “protection” as on a smartphone, so the justification that all apps need to be checked for malware doesn’t exist on this platform. This was a chance for Apple to break with the past. It’s chosen not to do so.

- I wonder if, strategically, Apple has ended up “skating to where the puck was” rather than where it’s going to be. It’s taken so long to get Apple Vision out – by some reports, perhaps ten years – that the interest in and relevance of VR and AR has died down. VR’s use cases have mostly boiled down to games. AR is still not really a possibility, at least not in its ultimate form.