Google lies

If you are interested in any way in the worlds of SEO -- black, white, and every shade in between -- you are going to be aware of the massive leak of what looks like internal documentation about search. For an SEO, this is almost Holy Grail level stuff. Although it doesn’t detail how or even which of the factors that Google is collecting data on determines the rank of an individual page, it’s safe to say that it’s all in here, somewhere.

A lot of the initial focus of posts about the leak has been on the fact it shows that many of the factors Google has consistently claimed not to use for ranking signals are, in fact, being collected -- and so are likely to be ranking signals. This includes everything from individual author authority through to the overall authority of a site.

So... Google has been lying. But the reality is I don’t know a single SEO practitioner in the publishing space who believed this stuff anyway. We all knew that making it obvious that a writer had authority in a particular topic would gain you ranking. We all knew that sites themselves had some kind of measure of authority. We all knew that freshness matters (who amongst us has not gamed updates to increase the freshness of content?)

Everyone who has worked around the Google space has known which of the company’s pronouncements to take at face value and which to look at with a raised eyebrow.

I will leave it to others to pick over the bones of this and work out what matters and what doesn’t. While I still keep an eye on the SEO world, part of me thinks that the era of publisher SEO is drawing to a close, as traffic from search inevitably declines and Google turns from the world’s biggest referrer into the global answers machine.

Although its initial foray into AI answers on the page has run headlong into some issues, the direction of travel is clear. I would strongly advise anyone who is spending too much time snickering about dumb answers not to be too complacent. AI probably isn’t going to end up coming for everyone’s jobs, but sooner or later it is going to come for your traffic.

Weeknote, Bank Holiday Monday 27th May 2024

It’s been a while since I wrote a proper Weeknote. To be honest, I am struggling with them a bit – I’m working at an actual company four days a week, which means what I can talk about is a bit more limited than when I was just mostly home-working freelance.

The job is at a small business to business publisher and events company, working in the pharmaceuticals and transport spaces. Although I have touched on working with transport before, pharma is totally new to me. That’s not a big deal though: my role is to work with their content team, who don’t have a lot of experience, and get them working in new and exciting ways.

Experience is a strange thing. By any solid metric, I have a lot of it. I’ve worked many different roles in editorial, content creation, video, podcasting – if it’s a medium, I’ve probably done it. I’ve worked on print, digital, done audience development, SEO, social, and more. And I’ve run teams that varied in size from a handful of people to close to fifty.

Yet sometimes I feel like I don’t know what to do with that experience. Or rather: it feels hard to demonstrate to people just how valuable that experience is.

I have skills and knowledge that are timeless, but a lot of companies out there seem to overlook them. I have witnessed the evolution and transformation of many industries and markets over the past thirty years, but – perhaps because I have spent the last few years buried deep inside a big corporation – it’s sometimes hard to have much to show for it.

I have a wealth of stories and insights to share, and when I share them people value the insight, but getting the opportunity is sometimes more difficult.

But then I looked at Reddit posts from recent graduates, who all seemed to discover that the assurances of high salaries and good jobs they were given if they just graduated were, in fact, not bearing out. And I realise (again) how easy I had – and have – it.

Nearly 40% of 18-year-olds go to university. When I went, in 1986, that percentage was much lower – only 15% in 1980. Likewise, on my year only three out of 110 students in the cohort got first class honours – 2%. Now the average is 36%. When that many people are graduating, and that large a number are getting top marks, it’s not difficult to see how being a graduate isn’t the guarantee of a better job that it once was.

If someone with my experience and advantages doesn’t feel like he’s being heard, what chance do people just starting out have?

Ten Blue Links, All Your Computer Screengrabs Are Belong To Us edition

What a weird week. You might have noticed Microsoft had a few announcements. I’m not going to dwell on them – but what I will say is that moving AI from the cloud to the device while preserving privacy is hard, but a lot easier than keeping AI in the cloud. And so to the links…

1. Privacy sandbox is coming, and publishers might be in (more) trouble

Does Google hate publishers? You should know all about “privacy sandbox”, its not-really-private way of using aggregate data to target ads to people, which will just cement its position as Lord of The Ads. One thing that still isn't clear is if, in fact, publishers that don't use it will get downranked in search. At a time when AI answers and Google's general love of all things Reddit are already making them suffer. It will neither confirm or deny this. Which usually means it's going to do exactly that. If you're a user, Kagi is over there (and it's incredibly good).2. Speaking of the media apocalypse…

This is one of the most depressing things I have read in quite some time. Audience from social media: dying. Audience from Google: dying. CPMs: Hilariously bad. One slight positive: Journalism has always existed with various business models, and it's not always been about scale and advertising.3. Ben and Satya talk cricket. Oh, and AI

I've always loved Ben Thompson's work, even though I often don't agree with him these days. This long interview with Satya Nadella is worth a read in its entirety, and no, it doesn't feature cricket. Well only a bit. Related: I recently set up a new PC. What sport did it automatically show me in the widgets? Cricket. I see what you did there, Satya.4. Twenty-four hours

Did you know that the Japanese used to have their own system of timekeeping which had longer or shorter segments depending on the time of year? And they built beautiful, elaborate clocks to tell time in it? I didn't, and now I really want to use that time system myself.5. Not sent from my iPad

MG Siegler -- who, I am glad to say, is back writing regularly about tech -- hits the nail on the head about the latest iPad, and iPads more broadly. It's frustrating when you hit a wall with software like Safari, and you hit a wall far too often.6. Reading comprehension and the age of AI

It's not just AI that threatens the truthfulness of our politics and culture: we have also lost, in some cases, the ability to read and comprehend long-form, detailed content. We have become the tldr; society.7. The coming apocalypse in UK universities

Unless you work in the sector, you might not realise quite how stuffed UK universities are. And when I say “stuffed”, I mean “pretty close to technical bankruptcy and no longer able to carry out their core function”. It's yet another thing which the inevitable Labour government is going to have to pick up and fix, with both short and long-term measures required.8. No, today's AI isn't sentient (but this article is rubbish)

There are few people with any knowledge of AI who claim that today's large language models (LLMs) are sentient, but that's the straw man this article starts with. Worse, though, is to follow. Despite it being co-written by a proper professional philosopher, the writers seem blissfully unaware that its insistence human-style embodiment is required for AI is one of those points that has been debated for longer than computers have existed. Read, but then read some proper philosophy of AI.9. Media companies are making the same mistakes with AI they make with all new tech

Jessica Lessin has written a good piece for The Atlantic on how media companies' rush to make deals with the likes of OpenAI to provide access to their content is short-sighted and stupid. She's right: it is. When are media companies going to learn that when tech companies refer to “media partners” they mean “suckers”?10. How do you become a writer? You write

Oh Ursula, how right you were. She was talking about fiction, but the same is true of any kind of writing. How do you become a journalist? Write journalism.Hate to say I told you so

I don't think I was the first person by a long way to draw the conclusion that AI posed an existential threat to the publishing industry. While far too many publishers took one look at large language models and saw a way to make the cost of content significantly cheaper, my background in audience development told me straight away that the ability of LLMs to ingest content and spit out a summary was going to fundamentally change search engines, to the long-term detriment of publishers. Why click on a link when Google can give you an answer?

Ben Thompson – still one of the sharpest commentators on the relationship between tech and media – this the nail on the head when he talks about LLMs as an extension of aggregation theory:

LLMs are breaking down all written text ever into massive models that don’t even bother with pages: they simply give you the answer.

Google's announcement at Google I/O that it would roll out AI Overviews on search pages in the US seems to have finally got people's attention. Google is, of course, claiming this will increase clicks to publishers, which seems barely credible -- and the fact it's not giving publishers any way to see if a click originates from AI Overviews in Google Search Console suggests it really doesn't want anyone measuring that claim.

And don't think as a publisher you can opt out. The only way to do that is to opt out of search entirely. While you can opt out of being crawled for use in the Gemini chatbot, you can't opt out of AI Overviews on its own.

Gartner estimates the fall in traffic down to having AI-driven answers on the results page at between 35-60%, which would be a catastrophic fall for most publishers.

I think this is only the start: AI answers are not conversational, and for many situations – especially purchases – a conversational interface is generally superior to a simple text search. Turning search into a conversation is a huge step and it's likely to further impact publishers as a new generation gets used to "talking" to a machine to get exactly the answer they want.

So what should you do? The only way forward is to build direct audience, and focus on owning the relationship between you and the reader without being mediated by the large platforms. That may mean subscription - but it could also mean focusing on a smaller but highly valuable audience, wether that's a niche in the B2B market or focusing on building community rather than giving answers.

Treat your existing ad revenue and affiliate revenue as a cash cow, not a growth market. Although my gut feeling is that AI Overviews won't impact on affiliate content as heavily as the kind of answers-based pages which have been big traffic drivers for the past few years, their time will come too.

Be entertaining – remember that audiences don't just read content for information, they want to be entertained, provoked into thought, and to come away from an article or site feeling like it's really delivered. That probably means raising the quality of your writing – think New Yorker or The Verge.

But most of all: be yourselves. Don't try and be anyone else. For as long as I've been in publishing one of its scourges has been the reverse of "not invented here": a kind of belief that competitors are somehow ahead of you, that they have their strategy straight while you're still stuck in some kind of technological or content strategy dark ages. It's never been true: everywhere I've worked has felt the same way about whoever their competitors were.

You need to know your audience better than Google does, better than Facebook does. Can you do that? I think you probably can.

Some thoughts about Apple’s new iPads

Mark Gurman’s last minute “maybe an M4…” rumour turned out to be absolutely correct.

No one would have batted an eyelid had the company gone with an M3. Instead it chose to skip a generation and bring a new generation of its processors to the iPad before the Mac. The unanswered question (so far) is why?

My gut feeling is there are several drivers for this decision. First, it allows TSMC, who will be manufacturing the M4, to start with relatively small volumes. iPad’s sell well: iPad Pros, on the other hand, are a smaller part of the mix, and probably lower volumes than the MacBook Air or low-end MacBook Pros, which would have been the other option for a new chip.

Second, there is probably a performance price to be paid for that “tandem OLED” screen. Tandem OLED, by the way, is not a new thing. As reported by The Elec back in 2022, it looks like Samsung could be the manufacturer although LG Display also makes tandem OLED, mostly for the automotive market. In addition to brightness, tandem OLED gives increased lifespan and better burn-in resistance, both of which are important with a device that’s designed to be used for long periods of time.

But third is the marketing factor: by putting M4 first in the iPad, it shows that the iPad is still an important platform for the company.

One small point of note: Apple talks about M4 having “up to 10 cores”, but some models have less. The iPad Pros which have less than 1Tb of storage use a nine-core M4, and get 8Gb of RAM rather than the 16Gb of the high-end models.

This makes sense, because those iPad Pros with 1-2Tb of storage are going to be bought either to do video or because the customer has a stupid amount of money and wants “the best”. But Apple is not particularly transparent about this: go to order, and you won’t find a mention of the difference.

Of course there’s a new Apple Pencil Pro, but the second generation Apple Pencil, which a lot of current Pro owners will have, doesn’t work with it (the lower cost USB-C variant does). That means an even more expensive upgrade for existing users, who will also need to buy a new Magic Keyboard.

More importantly than the cost, Apple had a chance here to make a point that the iPad’s modular nature means you don’t have to throw away your accessories every time you upgrade. It chose not to do that, and that’s disappointing.

Another trick that Apple has missed is not improving the battery life, which remains at the usual “ten hours” or “all day battery”. And it’s not that iPad is bad on this score. But the Mac is now so much improved that it’s no longer the go-to device if you want something which is going to reduce your charging anxiety to nothing.

I’ve said it many times now, but the M2 MacBook Air has been a revelation. It turns my computer from being something where I needed to ensure I had a charger with me to a device that gets charged overnight, like my phone. For someone whose first laptop got a couple of hours that is a huge mental shift, so much so that it took me a while to racing to the nearest wall socket once I saw the battery monitor drop down to 50%.

Battery life is the biggest factor which keeps me using the Mac right now. The iPad should get the same length of use, and it just doesn’t.

The iPad Pro’s place in the universe

For a lot of us, technology is as much a hobby and a passion as a tool. We love computers because we love them as objects, not just because of what they allow us to do. I fell in love with the iPad in this way from the first day I got my hands on one, in a car park in Basingstoke where I bought a first generation one for cash from a guy who had just come back from a US trip, before they were released in the UK.

Apple often talks in a way which makes my marketing-cynical eyes roll, but its description of the iPad as a “magical sheet of glass” is, to me, real. A computer that’s just a piece of glass, that you can use as a slate when you want, as a creative powerhouse, as a book, as a TV, and that is capable of transforming its physical form by use of accessories to do all those things well – that’s something amazing.

The iPad should be that one device but somehow, 14 years down the line, it’s still not. My gut feeling is this comes down to the restrictions which Apple continues to place on what developers (and customers!) can do with it compared to the Mac or any real computer. All of the arguments people make about customer benefits to a locked-down ecosystem don’t apply to a computer which is designed to be your main device.

About that ad

I don’t think I have ever known Apple apologise for an ad before. It has quietly withdrawn them (including the What’s a computer? iPad ad, which I liked but you won’t find now on an Apple channel), and it has had duffers that it would rather people didn’t remember.

Like John Gruber, I didn’t really think it was that bad on first viewing, although it did strike me as pretty tone deaf. It definitely didn’t get the message across, which was that the iPad can be all these wonderful creative things. Instead, it focused on the destruction of creative things, which isn’t “at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts” at all.

But thinking about it more, Apple should have predicted the reaction to it. It isn’t the plucky underdog anymore: it’s one of the biggest technology companies in the world, and people are (justifiably in my view) wary of it because of that. Where perhaps 10 years ago people would take its environmental claims at face value and believe it’s control freakery was down to a desire to deliver the best experience for customers, now less people want to give it the benefit of the doubt.

Including, of course, me.

Ten Blue Links, "Did they really crush that lovely piano?" edition

1. Yes, Apple, we're also talking about you

Cal Newport reckons that it's time to dismantle the technopoly. Taking a cue from Neil Postman's (great) book, he defines this as the “submission of all forms of cultural life to the sovereignty of technique and technology.” Postman was writing in 1992(!) but if you think about the technopoly as it exists today, we're really talking about how every single technical development is thought of as an unalloyed good, from AI scraping the whole of human knowledge to Apple crushing creative tools into a product it sells (at a 40% margin). We'll come back to that one later.

2. And speaking of dodgy corporate behaviour

Along comes Google, which – against the orders of the DOJ – routinely destroyed internal communications. The only reasonable conclusion is it did this deliberately. A fine will be just “cost of doing business”. It's time to dismantle corporate repeat offenders.

3. Maybe Facebook might end up interoperable

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has been a target of the far wing for a while, who see it as a charter for “big tech” to stifle their speech (which, of course, means not letting the right stifle the speech of its enemies). But as Cory Doctorow explains, it's also the only thing which stops big tech companies from censoring anything which might cause them to end up in court for libel. More than that, though, a case which is currently going through the courts might end up with Facebook and others being prevented from messing with tools which let you customise your feed on their services – for example, by filtering out all that “for you” crap which the algorithm wants you to get angry about.

4. This week's product I am a little obsessed with

An e-reader that's the size of a phone and runs Android? You have no idea how hard it is for me not to hit the buy button on this one.

5. Hey, so what about that Apple ad?

Like John Gruber, I didn't think too much about Apple's “crush” ad when it was shown as part of the introduction of the new iPad Pros (more on those anon). But the more I thought about it, the more I realised quite how tone deaf it was. The intention was to show all those wonderful creative tools being squished into an iPad, which could do it all. The execution was showing many lovely things being destroyed. How did that get past Apple's senior team? That's the bit which, if I were an Apple shareholder, I would worry about.

6. And so on to the product I'm not obsessed with

Yeah, new iPad Pros. Yeah, M4 processor. Yeah… same old iPadOS. For about the tenth year running, I'm left hoping this will be the year when Apple finally produces an operating system that can make the most of all that power. I suspect I'm going to be disappointed, again.

7. Tesla is doomed, redux

Honestly, if I held Tesla shares, I would be looking to sell them at the earliest opportunity I could take a profit. Unless Western governments intervene plenty of car companies will go to the wall because when it comes to quality EVs, Chinese manufacturers are miles ahead. So why am I mentioning Tesla is particular? Because it's vulnerable, and the stock is still massively overpriced because Musk has managed to convince suckers investors Tesla is a tech leader.

8. Where the world of scams is going

It's going to get really bad. Five years from now, this kind of fake person attack will be both commonplace and convincing, and I really don't know how we combat it.

9. You can't have it both ways, Elon

“X Corp. wants it both ways: to keep its safe harbours yet exercise a copyright owner’s right to exclude, wresting fees from those who wish to extract and copy X users’ content.” This is another example of how the safe harbour provisions of US law for internet companies are a double-edge word. On one hand, they protect them from libel based on what their users say. On the other hand, they can't then claim all the intellectual property rights over that content as if they were publishers. X Corp isn't the only company to want a smorgasbord of rights, though: Meta had previously made the same kind of claim, and lost.

10. “Blockchain Rasputin over here is mad that moderation exists”

Headline of the week, easily. Moreover, Jack Dorsey man, WTF happened?

That time in the 90s I persuaded a Japanese film crew that my friend was Richard Branson, inadvertently foreshadowing the “geek pie” incident in “Nathan Barley”.

On the iPad becoming a Mac

Jason Snell wants the iPad to be able to be a Mac:

The iPad no longer feels like the future of computing, and that’s fine. The Mac is here to stay, something that didn’t seem like a sure thing five and a half years ago. It feels like it’s time for Apple to accept this state of affairs. macOS isn’t just one of Apple’s platforms—it’s a feature, a secret weapon that it can use to make all its other platforms more powerful when they need to be.

I don’t have any idea if Apple really has any intention of letting macOS run on other devices, whether it’s an iPad or a Vision Pro or even an iPhone plugged into an external display. But it seems to me that if there’s any Apple product that is flexible enough to make it work, it’s the iPad Pro.

I was a big iPad Pro user for quite a while, and a proponent of its simplified but powerful operating system. There are plenty of apps on the iPad which are brilliant, and developers have done a lot with the platform.

Since I got an M2 MacBook Air, though, my use of the iPad Pro has fallen away almost to nothing. While Apple has long billed the iPad Pro as its most versatile computer, capable of being a tablet, a laptop, or whatever, when it comes to the most important thing of all – software – the iPad isn't versatile enough.

I can't install another browser which uses a different rendering engine. All browser plugins have to be installed via an app store. I can't get software of any kind from anywhere except an app store. Although the file system has improved, it's still limited compared to that of a more open platform like the Mac.

And of course, if I ever decided I wanted to take my expensive piece of hardware and install a completely different operating system on it, well… tough.

When people talk about wanting the iPad to be a Mac, what they're ultimately saying is they want the platform to be more open because all of the decisions that Apple has made which lead to it being inferior to the Mac are about keeping it more closed. And I'm going to hazard a guess, given the way Apple has had to be dragged through a legal process just to open up a little, that's not on the company's agenda.

But I would love to be proved wrong.

I’m sure that Nick Bostrom’s move from AI doomer to “maybe AI is going to save us” has absolutely nothing to do with AI making a lot of money for people who he wants to fund him.

This sounds bad, but kudos to Dropbox for being transparent about it – and from what they say it sounds like other services (i.e. storage) were not affected.

One of these days I am going to have to write up how I’ve turned Obsidian into the best environment for writing I’ve ever used. Today is not going to be that day though.

Ten Blue Links, Sunday rail replacement bus service edition

I managed not to do any writing at all this week, as I'm off work over the coming days and so didn't have a lot of time. But I can't miss out on my link blog because if I did, the backlog of fun things to write about next week would end up so big I would have to make it 20 blue links. And who wants that? So here we are.

1. Microsoft takes security seriously (again)

Anyone old enough to remember Windows in the 90s knows what an awful, insecure mess it was. In 2002, Bill Gates sent out a memo on “trustworthy computing” and, within a couple of years, Windows security had improved massively. Now, Satya Nadella is doing the same thing – but his memo isn't quite as good. It's overdue: Windows has, once again, become a buggy mess and where there are bugs there are security holes. Why now? Mainly because putting AI into Windows will be the foundation of keeping people on the platform, so an insecure Windows is, once again, a bad thing for Microsoft.

2. Why I don't trust Google with my files, redux

It's not just that I don't trust Google not to scrape the content I create to build some mega profile of me and target ads. Heck, thanks to NextDNS and uBlock Origin, I don't really often see ads unless I want to. It's that I know creating content where you don't have a local backup is a bad idea. And this is why. Yes, you can use Google Takeout to export your Google Docs into formats that other apps can read, but for all that is holy, please don't use their web apps to write the only version of your novel. If you really want to use a browser to write, sign up for a free Nextcloud account and use Collabora Office, which saves files as OpenDocument by default.

3. Hell freezes over

I have always had a lot of time for Paul Thurrott. He's been writing about Microsoft for almost three decades and has always been an unapologetic fan of Windows. But he's also a strong critic of some of Microsoft's business practices, and he's not afraid to talk about the enshittification of Windows 11. And now he's reviewed a 15in MacBook Air and loves it. Everything that Paul says tallies with my experience on the 13in Air. It's an absolutely joyous machine to use, although the base model doesn't have enough storage (forget the complaints about 8Gb memory, for the usage that you're going to put this machine to, it's fine).

4. And they wonder why people are “quiet quitting”

As I occasionally say to young journalists, you owe the company that you work for precisely nothing apart from the work you're contracted to do. If someone comes along with a better offer, don't think you should stay because of “loyalty”. While no employer, I have ever worked for likes laying people off, or in fact has done it except where there's been good reason to do it, neither will any employer avoid making you redundant because you're “loyal”. This person at Tesla seems to have found that out the hard way.

5. Fusion failures

There is no one better at writing about the core technology in the Mac than Howard Oakley, my former colleague at MacUser who spent several decades writing the help section. I don't know how many readers Howard saved from some kind of technical jam, but it's a lot. Howard probably knows more about the Mac than anyone outside of Cupertino (and most likely quite a lot more than most inside Cupertino), and this example looking at the technology of Fusion Drives (and why they fail) is a good example. He's also one of the nicest people it has ever been my privilege to work with.

6. Fast fashion is bad, and Shein is the baddest

OK, maybe not the absolute worst, but there are good reasons to never buy anything from Shein if you want to avoid things like forced labour and the destruction of the planet.

7. And speaking of brutal companies

There are so many reasons why Amazon should be broken up, but this look at its absolutely atrocious business culture and ethics just adds to the pile.

8. You never think it will happen to you, until it happens to you

Gen X -- my people! -- are apparently finding it really tough to get jobs, thanks to a combination of ageism and, well, more ageism. We are, apparently, set in our ways and expensive, which means no one wants to hire us. And, of course, women get it worse than men.

9. The cost of doing business

The headline on this piece from Om says it all: “billions in profits, millions in fines”. Fines will never keep pace with the money that tech and comms companies can make from abusing customers. Only break-ups and active restrictions will ever work. I can't think of a single example where a mere fine has caused a tech business to change its ways.

10. Tech journalism, or just “journalism”?

I left this one until last, and it's a great piece: Asterisk Mag has had a look at the quality of technology journalism in the mainstream and found it wanting. It notes that it often focuses on scandals, personalities and sensationalism due to competitive pressures in the media industry, rather than, you know, actual insight into tech. And they are right, but I think even if you look outside the mainstream it's pretty dire. Try reading the kind of in-depth technical analysis you got in Byte magazine and then looking through even Ars Technica (which is good by today's standards) and you can see the difference. This is mostly down to economic pressure: at least from the perspective of journalists themselves, research shows that when times are tough, quality declines. And times, now, are very, very tough indeed.

Why do people try and forbid linking?

Websites That Forbid Other Websites From Linking to Them – Pixel Envy:

Some of these are even more bizarre than a blanket link ban, like Which? limiting people to a maximum of ten links to their site per webpage. Why would anyone want to prevent links?

I can actually answer this one: it’s an attempt (albeit pointless) to prevent sites linking in a way which Google will define as spammy. Low-quality backlinks used to be a bit of an SEO nightmare, and you used to have to disavow them as toxic in Google Search Console. More than ten links to the same site from a single page is classic link spam, hence Which?’s attempt to stop it.

Ten Blue Links, “gosh is that the time” edition

1. Who among us has not been surprised by needing people to do things

Spotify's Daniel Ek is shocked, shocked I tell you, that laying off 1,500 workers has actually made the efficiency of his company worse. It's almost as if those people did things which were, perhaps, important to the business. Seriously though, if you allowed your company to hire 1500 people who weren't actually needed, then you're a bad leader and should pay the price for that. What actually happens because capitalism, is that the leaders get a bigger bonus for “taking the hard calls” even when it was their decision to approve those hires in the first place.

2. Just how bad are the tech barons?

Bad enough to want to subvert democracy and establish their own dictatorships. Balaji Srinivasan is one of the worst, but he's not alone in this endeavour: Marc Andreessen is equally awful. As an internet veteran, I always feel I should apologise that we didn't spot these men -- and it's always men -- were this terrible a lot sooner. But we were all carried away in fever dreams of tech utopianism for a while. Sorry.

3. Remember, a sustainable society is a bad society

Speaking of Andreessen -- yes, I know you don't want to, but to stop things going completely to shit, we must -- this article about a dinner with him is full of moments of hilarity and absolute horror. Here is a man with few redeeming qualities, who used government funding to create a web browser which he turned into a large pile of cash for himself, railing against the government. You might as well print t-shirts with his chubby, milk-fed face on it and the words “why you should be a communist” on them.

4. Speaking of cheating

The part of me that loves sensational counter-narratives would love this story to be true. Qualcomm cheating on the benchmarks for its upcoming “nearly as good as Apple's chips, no really, this time we're not lying” Snapdragon X Elite would be a fantastic scoop. But I don't believe it. Why not? Simply because the stakes are too high, and the rewards too low, for it to be worth Qualcomm doing it. As soon as the new ARM-based Windows computers come out, everyone will benchmark them, and if they don't perform anywhere near as well as touted, the company will not get another chance.

5. That sound you hear is your old iPhone being shredded without mercy

When you trade in an iPhone for recycling, it's basically shredded. Why? Because Apple desperately wants to avoid parts from old phones getting back into the market to be used for repair by third parties, who will do the job more cheaply than Apple. Why does it want that? Because it wants you to buy a new iPhone, rather than getting your perfectly good one repaired. If there isn't a more obvious symbol of why the present system is broken and isn't going to stop climate change, I don't know what it is.

6. I feel seen

I posted about this one all over the social medias but reading it back again it still hits home. I'm in the home stretch of my career, too, and the best advice I can give anyone is to realise early on that some day your career will end. Don't get so drawn into it that you have no idea what to do when it does – or how to wind it down gently.

7. The man who killed Google search

It's a beautiful shared truth that Google's search has, for the last few years, been getting worse. You'll hear it from experienced SEOs, publishers, and normal users too. But why has it happened? Ed Zitron wrote a good piece which not only explains the “why”, but accuses the “who”. The key question now is: How does Google get out of this mess – and, in fact, does it even want to?

8. And speaking of dreadful corporate behaviour

HERE'S GOOGLE AGAIN! Like lots of corporations, Google had rules about how its suppliers treated their workers. Unlike plenty of corporations, as soon as that became a problem, it changed the rules so it could work with suppliers who paid worse wages, didn't provide health insurance, and so on. Google, of course, is blaming someone else – in this case the National Labor Relations Board, which ruled that these rules meant Google was effectively a co-employer of its partners' staff. Blaming other people is, of course, standard corporate behaviour these days. Corporations who want to take responsibility for their actions are a dying breed – if they ever existed at all.

9. I will laugh so hard I'll poop

Could Tesla go bankrupt? Motorhead neatly avoids Betteridge's Law by adding “The odds are rising” on to this headline, but I would have been willing to extend an indulgence to them because yes, Tesla could indeed go bust. The company has a weak product pipeline – the Cyberdog… sorry Cybertruck is a distraction – and its share price has collapsed because it's no longer considered a growth stock. This is why Musk is desperate to pivot the company so it's seen as an AI leader, which would hitch it firmly on the latest bubble of excitement rather than the old hat that is electric vehicles.

10. And speaking of Elon

Former US secretary of labor Robert Reich points out the obvious: that what Elon Musk indulges in isn't capitalism. Essentially, it's extortion.

Weeknote, Sunday 21st April 2024

This has been a week of feeling my age – but also wondering exactly what that means.

I'm currently working with a small editorial team who are, pre-dominantly, quite young. Like “born this century” young. That in itself is a strange feeling because knowing people who were born in the previous century has never been part of my experience. The oldest person I remember when growing up is my grandmother, who was born in 1910: although I'm sure I met people born in the 1800s, it never really registered.

It shouldn't make a difference. And yet, there is something about the turn of the century that marks a change, so working with people for whom the 20th century is nothing more than history feels strange. Particularly when someone refers to “vintage music” and they mean “stuff from 2005”, as happened to me this week.

I read Simon Kruger's excellent piece on finding yourself in the home stretch of a career race, and it has prompted more thoughts than I care to have about my life. I am at the very stage that Kruger describes, “the antechamber between work and pension” where your world starts to change whether you like it or not.

Your network of work contacts declines as people either retire, die, or just check out of the industry you're part of. For me, this is exacerbated by the decline of publishing as a business: most of the people I know who are around my age are gone from it because when an industry contracts it loses its most experienced people first.

I didn't really even choose journalism as a career. In a sense, it picked me. When wrapping up my PhD, I knew what I didn't want – to be an academic – but had no idea what I did. When the opportunity to join MacUser magazine appeared in Media Guardian (essential Thursday reading for the humanities student) it seemed like someone had created a bespoke job for me. Writing, technology, and – as I swiftly found out – daytime drinking were all interests, ones which were well served by technology publishing at the time.

Finding out I was good at it was a surprise. Finding out that I was also good at leading people was another one. But at no point at all did I think about whether that was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

I suspect that's in part because “the rest of your life” is too hazy a concept when you're in your 20s and 30s to make any logical sense. For me, it didn't really appear as a concept until I was in my 50s, when “the rest of your life” became an alarmingly short amount of time. “Slowly, and then all at once”.

Things I have been writing

A busy week for non-fiction, and a slow one for fiction. I wrote a very short piece which was basically me rolling my eyes at people who should know better. There was a Ten Blue Links post – and I think my link blog is getting well into its stride. And more substantive, I wrote about John Gruber's approach to privacy and antitrust.

Fiction-wise, I wrote a small piece of micro-fiction about death, and that I liked enough to think about expanding into a proper short story. I like writing micro-fiction, but ultimately, I think they are the equivalent of a yawn and a stretch when you wake up. And exercise, valuable, but not substantive.

Things I have been reading

For the past few weeks, my reading has been all over the place: some days pass without a book being opened, some are nothing but a book. I have been dipping into Julian Barnes' Through the window quite a bit, though. I love Barnes' non-fiction more than his fiction. He's a stupidly clever writer.

Informed Consent and Privacy – Pixel Envy

Informed Consent and Privacy – Pixel Envy:

Meta is probably one of the more agreeable players in this racket, too. It hoards data; it does not share much of it. And it has a brand to protect. Data brokers are far worse because nobody knows who they are or what they collect, share, and merge.

This is a point that I have made in the past: while the big companies like Meta get a lot of attention (and rightly so) data brokers further down the advertising food chain do a lot, lot worse things. That’s not to say “do nothing about Meta”, but it’s an important point to note.

Did IQs drop sharply while I was away?

AppleInsider: –"EU's antitrust head is ignoring Spotify's dominance and wants to punish Apple instead":

Speaking to CNBC the EU's Margrethe Vestager said her office was continuing to investigate Spotify's complaint that it is being prevented from reaching its audience. Spotify is currently the leading music streaming service in the world, while Apple Music is variously in fourth or fifth place.

Repeat after me: Spotify is not a gatekeeper. Apple is. Special rules apply to gatekeepers to stop them using their market power in one area to distort a free market in another.

This is not rocket science, and I'm at the point where I think if a journalist is getting it wrong, they're simply propagandising for Apple, Meta, or Google.

Ten Blue Links, “my, how you have changed!” edition

1. Four years is a long time in tech punditry

I'm going to break one of my self-imposed rules and include a link to a piece I wrote, on how John Gruber's attitude towards Meta's privacy-violating monopoly has changed over the past four years. You can work out what changed John's mind. I couldn't possibly comment.

2. Why we do reviews

It's not for of the companies whose products we look at. Back when I was starting Alphr, MKBHD was one of the reviewers we looked to as the gold standard: approachable, accurate, personal. Nothing has changed on that score, he's still superb at what he does.

3. This week's “no”

4. The rot economy is real

Ed Zitron has been writing so much good stuff lately, and this piece delivers. As he notes, venture capital doesn't reward “good” companies – it rewards companies that can be profitably flipped. The system is broken.

5. Tesla was always a bubble stock

The Wall Street Journal does something that's long overdue and has a look at the inside story of Tesla's fall to earth. Technology companies are often valued by their potential for future growth, and Tesla was no exception. But at one point it was also valued at more than the rest of the car industry put together. That's well beyond potential future profits and into bubble territory – unless you believe that at some point in the future, Tesla would have had a monopoly on cars. Now, of course, it faces competition, and unsurprisingly, the traditional carmakers build better quality vehicles than Tesla, and the Chinese companies build them cheaper AND better. Even Elon Musk's ability to make himself the main character every day isn't going to save them.

6. The internet is broken

“Your Uber driver is lost because his app hasn’t updated and keeps telling him to turn down streets that no longer exist. You still give him five stars.” File this under “I wish I had written it.” Brilliant.

7. There is no EU cookie banner law

No, really, there isn't. I think the biggest mistake of GDPR was not being tough enough.

8. CEOs are just as dumb as everyone else

Just as likely to fall for conspiracy nonsense, just as likely to repost it. And in tech, they're terminally online, too, which makes them even more likely to fall for bullshit.

9. Welcome to the new feudal era

If you want a clear explanation of how and why we are falling back into feudalism, Cory has you covered. This is why the EU DMA is so important: it's an attempt to wrestle us back from the edge of rentiers and liege lords and into competitive markets again.

10. Nilay

If MKBHD was one of our touchstones when building Alphr, The Verge was the other. This is a great, long interview with Nilay Patel, AKA the smartest man in tech journalism. If you're in any kind of journalism, you should read it.

What a difference four years makes

John Gruber in 2020 on the tracking industry led by Facebook:

The entitlement of these fuckers is just off the charts. They have zero right, none, to the tracking they’ve been getting away with. We, as a society, have implicitly accepted it because we never really noticed it. You, the user, have no way of seeing it happen. Our brains are naturally attuned to detect and viscerally reject, with outrage and alarm, real-world intrusions into our privacy. Real-world marketers could never get away with tracking us like online marketers do… Just because there is now a multi-billion-dollar industry based on the abject betrayal of our privacy doesn’t mean the sociopaths who built it have any right whatsoever to continue getting away with it. They talk in circles but their argument boils down to entitlement: they think our privacy is theirs for the taking because they’ve been getting away with taking it without our knowledge, and it is valuable. No action Apple can take against the tracking industry is too strong.

John Gruber in 2024, on the EU's actions which limit Facebook's ability to track users:

What makes this all the more outrageous is that many major publishers in the EU use this exact same “pay or OK” model to achieve GDPR compliance — and none offer a free alternative with non-targeted ads. Don’t hold your breath waiting for Der Spiegel to offer free access without ads. Christ, they don’t even let you look at their homepage without paying or consenting to targeted ads. And Spotify quite literally brags about its ad targeting. But Spotify is an EU company, so of course it wasn’t designated as a “gatekeeper” by the protection racketeers running the European Commission… They’re not saying “pay or OK” is illegal. They’re saying it’s illegal only if you’re a big company from outside the EU with a very popular platform.

I wonder what happened to turn John's attitude from “no action Apple can take against the tracking industry is too strong” to defending Facebook's “right” to choose how it invades people's privacy? Or is he suggesting that a private company is entitled to defend people's privacy, but governments are not?

And John's second point about Spotify fundamentally misunderstands the nature of antitrust law in general and the EU gatekeeper system specifically. In competition, actions which are legal when you're not a monopoly become illegal when you are a monopoly.

In particular, Apple – and Facebook – are gatekeepers because they “are digital platforms that provide an important gateway between business users and consumers – whose position can grant them the power to act as a private rule maker, and thus creating a bottleneck in the digital economy”. Spotify is not in that position. Der Spiegel is not in that position. Different rules apply – as they do to Tidal (not an EU company), and of course to the New York Times.

This really is not difficult to understand.

But underneath this in part is John's feeling that EU antitrust law is all an EU conspiracy to attack American companies. That would be news to Daimler, fined over a billion euros for an illegal cartel. It would news to Scania, fined 880m euro. To DAF, fined 715m euro. To Phillips, fined 705m euro. And so on. The EU fines European companies big sums of money all the time for breaking competition law.

The entire point of the EU is to create single, competitive markets. It does not allow big companies to “own” markets because free markets (in the EU's eyes) are good, and privately owned ones that allow big companies to stop being capitalists and act like feudal lords are bad. Facebook, Apple, and the rest have been doing this in digital for a long time, and the EU has decided it's going to stop.

On the fine art of technology reviews

Nearly thirty years ago I reviewed my first product. It was a Lexmark solid ink inkjet printer, created for designers to do lower-cost but higher quality proofs than were possible on the regular inkjets, expensive colour laser printers, or super-expensive Chromalin machines of the time.

Its launch was also the first press conference I went to. I remember nothing of the event, but I do distinctly remember meeting some of the trade press journalists from the magazines about printing (trade press was VERY large) who promptly took me down the pub. I spent a happy couple of hours getting paid to drink in the middle of the day, and realised I had found my ideal job.

I have no idea how many products I have reviewed over the years, but it’s likely to be several hundred single reviews and even more if you count group tests. All of which makes me think that I know a bit about reviewing.

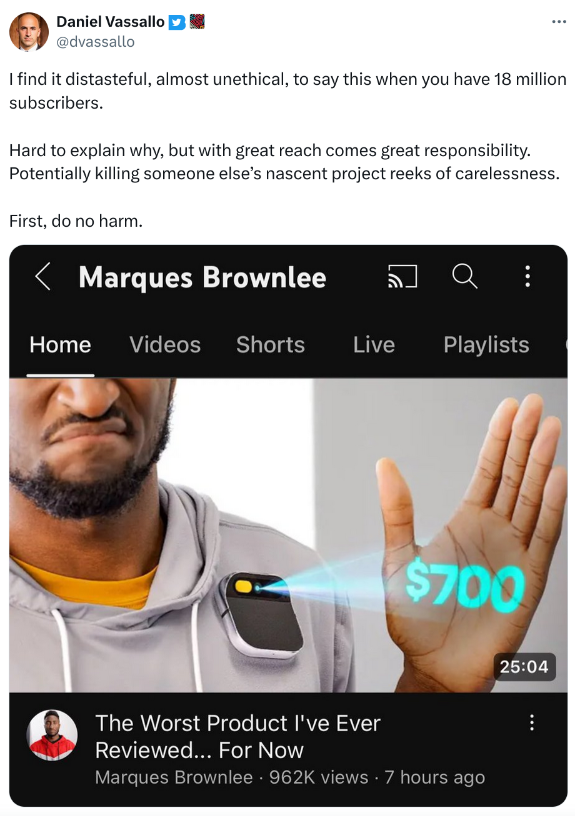

Unlike Daniel Vassallo:

“First, do no harm” is not a principle that can or should ever be applied to reviews. “First, tell the truth about the product”, on the other hand, is absolute the reviewer’s mantra. You owe nothing to the people who made the product. You owe everything to the people who might consider spending their hard-earned money on it.

Ben Thompson hits the nail squarely on the head:

“Who, though, is to blame, and who benefited? Surely, the responsibility for the Humane AI Pin lies with Humane; the people who benefited from Brownlee’s honesty were his viewers, the only people to whom Brownlee owes anything. To think of this review — or even just the title — as “distasteful” or “unethical” is to view Humane — a recognizable entity, to be sure — as of more worth than the 3.5 million individuals who watched Brownlee’s review.”

Vassallo has taken something of an online beating for this. The idea that telling the people who ultimately pay your wages – those who read your content or watch your videos – the truth about a product is “almost unethical” is indicative not just of Vassallo’s views, but those of the tech executives who have grown up in the last 20 years. The fact that the Humane AI Pin is a lemon is not MKBHD’s fault.

But Vassallo is really just expressing a view that’s part of the present Silicon Valley/venture capital paradigm. Why make a great product when you can make a so-so product and erect moats which turn into monopolies, locking customers in? The Rot Machine is real, and once you buy into it as a business model is not love of great products but a mastery of the mechanisms of stopping people going elsewhere. Customers become users, and who owes users anything? They just use what you supply, and should be grateful for it.

What technology companies hate is that good reviewers have power. And they wield that power not for the company’s investors and shareholders, but for the people who have to work hard and earn money to buy their products. Excellent reviewers can even end up helping improve the products, as Walt Mossberg often did:

“XM is only one of dozens of companies that have redesigned products in response to Mossberg's unsparing criticism. RealNetworks overhauled its RealJukebox player. Intuit revamped TurboTax. Mossberg even forced Microsoft to scrap Smart Tags, which would have hijacked millions of Web sites by inserting unwanted links to advertisers' sites. Few reviewers have held so much power to shape an industry's successes and failures.”

No wonder this generation of tech entrepreneurs would rather that reviewers shut up and gave them four stars.