Why do people get the history of Apple so wrong?

Dave Winer (who really should know better):

Graham uses Steve Jobs as an example. He knew what was and wasn't an Apple product. A hired CEO would have to have that explained to him. Sculley, who Graham cites, is a perfectly nice person in my experience, had no idea how to deal with Windows. Very different from a consumer product like fizzy waterSculley ultimately ran out of steam, but in the time he was at Apple he also took it from an $800m company to an $8bn one. Meanwhile, Jobs was back in founder mode at NeXT where, having taken some of Apple’s best people with him, he created a computer that no one wanted to buy and an operating system that remarkably few people installed.

The Steve Jobs who went back to Apple was a different person from the one that left it, chastened by the experience of business failure. It’s an interesting question of parallel history but my thought is that had Jobs won the battle and remained CEO rather than Sculley, the kind of mistakes that he made with NeXT would have probably lead to Apple suffering the same fate as most of the early computer makers who didn’t move to DOS/Windows.

DOJ, Nvidia, and why we restrict monopolies

A 1600, a group of English merchants were granted a royal charter, a legal document which allowed them to venture to foreign lands and seek trade. This was a big bet: not only were the territories they aimed to trade in a long way from England, dangerous to get to and occupied by people who didn't necessarily welcome English traders, but they had to invest £68,000 in the venture -- about £9m in today's money. For a period of 15 years, the royal charter granted them a monopoly on trade.1

The venture was the East India Company, later the British East India Company. By the mid-1700s, it accounted for half the entire world's trade. By 1858 it had a private army that was twice as big as Britain's, and ruled over the whole of what is now India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. That £68,000 bought its investors -- and Britain -- the biggest ROI the world has ever seen. The company turned a fifteen-year monopoly into an empire. If you want to understand the obsession that the Brexit-wrangling mouth breathers have with "Buccaneering Britain", look no further than the folk memory of the British East India Company.

This often comes to mind when I'm thinking about our modern technology monopolies. Like them, the East India Company founders took big risks – in fact, bigger risks than the likes of Mark Zuckerberg can ever conceive (no Facebook employee has, to my knowledge, been killed by cannon fire, even if, like the East India Company, their products have helped enable genocide).

Unlike those 17th century investors, the founders of modern monopolies are constrained by law rather than explicitly encouraged by it. We have, collectively, decided that there should be limits on the amount of wealth accumulated which monopolists are allowed to enjoy, and there should be limits to the power of corporations. Facebook, Microsoft, Apple and Google will, it's safe to bet, never be allowed a private army and the rulership of a big chunk of a continent.

In modern capitalism, taking risks brings rewards -- but only so far. And a dominant position, no matter how well-deserved, does not allow you the leeway to eradicate competition itself.

All this came to mind when reading Ben Thompson on the DOJ Investigating Nvidia:

Nvidia under Huang did everything we hope our greatest companies will do: they had a long-term vision, they innovated relentlessly to find new markets and applications for industry-leading technology, and when a world-changing opportunity presented itself with large language models, they were ready to take advantage of it, for a long-term benefit that may forever be unmeasurable. This is the behaviour our government apparently wants to punish?

Earlier this week, I listened to a great interview with Ben about on how he writes, which I highly recommend. In it, he noted his dislike of writing about antitrust:

“The one time I did almost burnout is like 2019, 2020. I was writing about regulation and antitrust and congressional hearings. And I'm like, oh, this is actually horrible. Like it's burning me out. I work a lot. That's not what's burning me out. It's writing about stuff that is kind of soul sucking for me from my perspective.”

I can tell Ben doesn't like writing about this stuff2, in part because I think he keeps missing a foundational point about antitrust: What's perfectly acceptable behaviour when you are a relatively small company becomes outright illegal (and rightly so) when you become dominant in an industry.

I'm not going to attempt to evaluate the merits of the DOJ case, in part because at present there is no case. Per Bloomberg:

"The US Justice Department sent subpoenas to Nvidia Corp. and other companies as it seeks evidence that the chipmaker violated antitrust laws, an escalation of its investigation into the dominant provider of AI processors. The DOJ, which had previously delivered questionnaires to companies, is now sending legally binding requests that oblige recipients to provide information, according to people familiar with the investigation. That takes the government a step closer to launching a formal complaint."

Seeking information about a company's conduct is precisely what the DoJ should be doing in any area where a dominant player is emerging, and the earlier it does that, the easier it becomes to make a case which has an actual impact. No one seriously doubts that Nvidia is now dominant in the market for AI processors. Is "AI processors" a market? Has Nvidia's conduct stepped over the line from tough competition to abuse of a market position? These are elements that an investigation should try to find out.

What the DOJ is clearly signalling, here, is it won't allow dominance to be abused even when companies have only recently crossed the line from being a competitor to dominance. Given the speed at which technology companies can distort markets and crush competition when they achieve dominance (who remembers DR-DOS?) this feels like a sensible approach. The other option -- giving businesses 10–20 years of the ability to destroy competitors not through making the best products but by sheer force of accumulated power -- has demonstrably stifled competition. And competition drives innovation (at least in theory).

Ben's best argument is that Nvidia has done nothing wrong, and in fact has done what we want companies to do: make long-term, industry - changing and fundamentally risky bets to achieve huge returns. And I agree! There is no doubt that Nvidia deserves the billions of dollars in profits it will make from being the biggest and best player in AI processors. The lead it has created from the investments it made will last for a long time, and generate a lot of money. Jensen Huang deserves all the credit he gets, and as many sharp black leather jackets as he cares to wear.

For anyone who has grown up in the era of the hero/founder and "startup in a garage" vision of Silicon Valley, I think it's a compelling view. Apple is another example. Under Steve Jobs, they made a series of "bet the company" product launches, culminating in the iPhone. They created a platform which over a billion people use globally, spending tens of billions of dollars a year on apps. Don't they deserve 30% of that, forever?

But one of the principles of Silicon Valley entrepreneurship was that success has to be continually earned. Andy Grove, who knew a thing or two about it, warned against "the inertia of success" because, even if you are at the top, you don't deserve anything unless you keep innovating, keep creating the best products. "Only the paranoid survive" because somewhere out there, a smaller, more nimble competitor is coming to eat you – and all your past success will not save you from that fate.

A company getting it right does not give it some kind of permanent licence to coast while printing money. The question that all antitrust seeks to answer is simple: how much is enough? When do the well-deserved riches and power that accumulate to companies that make big bets, execute well, and invest wisely start to be toxic for society or humanity as a whole, and for competition itself? Are the riches that the largest companies make earned, or are they simply the product of being large? If it's the former, great! But if it's the latter…

The founders of the British East India company also did everything we hope our greatest companies will do: they had a long-term vision, they innovated relentlessly to find new markets, and when a world-changing opportunity presented itself, they were ready to take advantage of it, for a long-term detriment that may forever be unmeasurable. Sometimes, enough just is enough.

Ten Blue Links, “I was a teenage anarchist” edition

1. Model collapse isn’t just for AI

When a large language model starts to ingest a lot of content written by either itself or other large language models, it falls into what’s called model collapse: a state where, like a snake eating its own tail, it no longer makes sense.

Back when I was working on the philosophy of AI in the 1990s, one of the strands of study was using computers to understand human behaviour by creating models and seeing if the quirks of us meat sacks would emerge from the model. And I would argue that model collapse is one of these quirks. If the information you are exposed to is limited to an echo chamber, then you see the same kind of behaviour in people.

Unfortunately – but predictably – the “super-smart” Silicon Valley billionaires are just as susceptible to model collapse as either an LLM or every other human. Only, unlike most people (and most LLMs) the damage they can do because of this model collapse is actually enormous. Musk, Andreessen, Thiel and the rest have created a model of the world which bears no relation to reality, but unfortunately, they have it in their power to influence the world so it matches their views.

2. RIP AnandTech

At its height, AnandTech was the best site around for deep, highly researched reviews of significant products. As such, it was an outlier as technology product writing moved to an affiliate-based revenue model which focused on lists of potential options for purchase. It had more akin to the technology publishing landscape that I learned the trade in, where products were tested (occasionally to destruction) in labs by people who focused on devising ever more fiendish methods of working out how a product would perform in the real world.

I’m sad to see it go, but at least it doesn’t have to suffer the same fate as so many other sites which have simply been used as fodder for boosting the SEO rankings of lesser brands.

3. Monoculture is mono failure

Diversity, as anyone smart knows, is strength. That applies to farming. It applies to organisations. And it applies to platforms. Diversity protects you from the impact of monocultures, which inevitably contain the seeds of their own downfall.

And yet, the technological systems we currently have implicitly rewarded monocultures, monopolies and monopsonies. Wherever you look, from hardware systems to social media platforms to online retailing, we are creating failure points through a lack of diversity. CrowdStrike is just the latest example, but 21st century capitalism’s addiction to the Highlander Principle (“there can be only one!”) is going to present some profound problems over the next few decades. Assuming of course we survive them at all…

4. I just wish Bluesky was actually a federated system

Bluesky, the “not Twitter” that isn’t either Mastodon or Threads, has seen an influx of users from both Britain and now Brazil as people become more and more annoyed with Elon Musk. But it’s also been focusing on some fascinating approaches to content moderation and protecting users. The latest is the ability, if a post of yours is quoted, to “decouple” the post from the quote – effectively stopping in its tracks one commonly used method of abuse, the “quote tweet pile-on”.

I still don’t like that it’s not, yet, truly federated: you can’t run your own server, and even if you use a name based on your own domain you can’t move servers no matter what. But I like that they are experimenting with different options.

5. JISC leaving Twitter

And speaking of leaving Twitter, JISC announced it would be ceasing activity on there. The organisation is “the UK digital, data and technology agency focused on tertiary education, research and innovation”, a non-profit which drives digital transformation in education in the UK. It’s a big deal that it no longer believes being active on Twitter is in alignment with its values.

6. The NeXT IPO that never happened

Via Michael Tsai, this is not only a great little potted history of NeXT, the company that effectively did a reverse takeover of Apple (and ruined my 30th birthday), but also reveals that it was at one point planning an IPO. The thing that made an IPO possible wasn’t the hardware (NeXT was out of that market) or NeXTSTEP/OPENSTEP. Instead it was WebObjects, the web development platform which made creating complex dynamic sites much more easy than before. At the beginnings of the Dotcom boom, this was a major potential business.

Extra bonus fact: Dell apparently used WebObjects to create its online store in just four weeks. That, at the time, was incredible.

7. Moof!

8. Starship Stormtroopers

I was far too young to read New Worlds magazine, but by my early teens I had moved on from Tolkien to Michael Moorcock, borrowing the Dorian Hawkmoon and Corum Jhaelen Irsei series from the local library and being absolutely amazed by the sheer muscularity of the writing. At some point – and I can’t remember where I found it – I read Moorcock’s “Starship Stormtroopers” essay on the fascistic nature of much of the Science Fiction canon, and that was it: my life – and my politics – changed for good. I became a teenage anarchist.

I’m not sure if I am still one today (the teenage bit, definitely not) but I occasionally reread the essay, just to remind myself that it’s OK Not To Like Frank Herbert.

9. The best novel about 21st Century male loneliness

The second of the holy trinity of New Worlds writers that changed my view of fiction was, of course, M John Harrison. There’s an argument to be made that Harrison is our best living writer, although I’m sure that he would hate anyone for making it. Harrison was unique at the time for not allowing genre to dictate what he should write, and Climbers, his 1989 novel about rock climbing in Yorkshire, saw him walk a long way out of science fiction without breaking a step. It’s a brilliant book, and I was really pleased to see this article which argues that it’s also become the definitive novel about 21st century male loneliness.

And I think it’s right: part of the impact of our relationships moving from primarily face to face to being mediated by the internet is, as Sherry Turkle put it, that we are alone together. In that sense, it mirrors the mental state of going climbing, which is a social activity done primarily in solitude.

10. Ignorance of your (global) culture is not considered cool

I think of myself as pretty well-educated. But I didn’t understand the role that India played in essentially creating the numbering system which we all used – I, like most, thought it originated with Arab mathematicians.

But it didn’t, and the forthcoming book by William Dalrymple about how India changed the world got ordered quickly once I read this article. And it is, as Dalrymple notes, ironic that the innovations in banking, accounting and business enabled by the Indian system of numbers when it reached the west did so much to create the financial muscle which allowed Europe to ultimately subjugate India. After all, it was “the East India Company – run from the City of London by merchants and accountants, with their ledgers and careful accounting – that ran amok and seized and subjugated a fragmented and divided India in what was probably the supreme act of corporate violence in history.”

Ten Blue Links, "Cthulhu lives!" edition

1. The smartest comment you will read about AI and art this week

From the wonderful Laurie Anderson, about an AI version of her late husband, Lou Reed: “I mean, people might have black-and-white photographs of their grandparents or even a VR representation, but nothing can capture these people. They’re dead. I like what the Dalai Lama said about an artificial flower being as good as a real flower, because it reminds you of the real one. I’ve done versions of Lou’s voice and Lou’s writing made from AI trained on his work. It’s not Lou but it reminds me of Lou. It’s about the reminding of how you feel about that person.”

2. There’s definitely a German compound word for this

What is a remembrance of futures which never happened called? This article about an edition of Saturday Review World which looked at the world of 2024 from the perspective of 1974 includes quotes from Wernher von Braun, Neil Armstrong and many others. I would love a copy.

3. Your occasional reminder that macOS malware exists

And this one is a data stealer, called — and I am not making this up — “Cthulhu Stealer”. You can’t get more scary than a bit of Cthulhu.

4. Adversarial interoperability made the computer we know and love

Every time I set yet another account of how antitrust is “stifling innovation” I am going to send this article to its author. Adversarial interoperability made the PC possible, stopped Microsoft completely owning all office documents, and helped save Apple. And now, thanks to extensions to IP law, it’s more than a little broken.

5. File under the dumb stuff that happens in app stores

Application developer makes a piece of software which allows people to use their existing account with Digital Ocean to do a cool thing. Apple nopes it because Digital Ocean isn’t paying them a cut of all their revenue, although the app isn’t made by Digital Ocean. Rent seeking, much?

6. Are we the baddies?

And speaking of Apple, this article sums up how, I think, many people are feeling about the company these days – folks who in the past would have not only been fans of the products, but also been evangelists for the way the company was different to the rest. This paragraph, in particular: “But another part is that despite achieving massive success, Apple continues to make decisions that put it at odds with the community that used to tirelessly advocate for them. They antagonize developers by demanding up to one-third of their revenue and block them from doing business the way they want. They make an ad (inadvertently or not) celebrating the destruction of every creative tool that isn’t sold by Apple. They antagonize regulators by exerting their power in ways that impact the entire market. They use a supposedly neutral notarization process to block apps from shipping on alternate app stores in the EU. Most recently they demand 30% of creators’ revenue on Patreon. No single action makes them the bad guy, but put together, they certainly aren’t acting like a company that is trying to make their enthusiast fans happy. In fact, it seems Apple is testing them to see how much they can get away with.”

7. I’m shocked, shocked I tell you etc

Who amongst us could possibly have predicted that the emissions claims of giant technology companies would turn out to be complete hogwash based on dubious accounting techniques. And that, in fact, their emissions have been steadily climbing even before the current vogue for carbon-hungry AI? (Via the super-smart Rachel Coldicutt.)

8. The best iOS is the one you can’t get, Americans

As Federico says, the fork of iOS that’s available in the EU is the best version of iOS.

9. Just in case you have forgotten how bad Microsoft was

Remember when Microsoft deliberately broke Windows if it was running on a competitor’s version of DOS? This is why you don’t let platforms have as much control as the likes of Google and Apple have today. It’s not that they’re bad people: it’s that all the economic imperatives are towards things which harm competition and so, over time, harm customers.

10. No

Ten Blue Links, "Gnarls Barkley is innocent" edition

1. Just because we killed you doesn't make us liable

Dr. Kanokporn Tangsuan died after eating a meal at a Disney resort. Her family claims this is down to an allergic reaction after the restaurant allegedly failed to label their food properly. So far, so tragic — but tragic in a completely normal way. What makes this incomprehensible, though, is that Disney's legal team have decided that a clause in the Disney+ streaming service's ToS — which one of the plaintiffs had trialled a few years ago — means the case can't be tried in a court. While this sounds extreme, terms of service are chock-full of this kind of stuff, all designed to create a parallel legal system that's easier for large companies to game to their advantage. Not content with having a legal system that's inherently rigged in their favour thanks to costs and their ability to lobby to have laws they don't like watered down, companies are trying to avoid any legal responsibility. Truly, we live in feudal times.

2. But wait, what's this coming over the horizon?

Finally — finally — though, big companies are getting held to some semblance of account. Last week Google found that just because you're acknowledged as the best product doesn't mean you can also pay potential competitors to ensure they don't challenge you. Cory Doctorow's talk at Defcon 32 outlines what's going on, and why regulation and law is the biggest sharpest tool in the box to ensure a competitive landscape in tech and elsewhere. Required reading.

3. You all know who Stanley Baldwin is, right?

Baldwin was the British prime minister who finally stood up to the press barons in the UK -- and won. That's a lesson today's leaders, including Keir Starmer, should take to heart. This article highlights European Commission Thierry Breton's public letter to Elon Musk as a similar moment. It is, of course, only part of Europe's ongoing campaign to make big tech companies actually follow the same laws as everyone else. You might agree or disagree with individual actions, but if you don't believe that companies should be subject to the law “without fear or favour” then you probably shouldn't keep reading this blog.

4. “Associated fees”

I genuinely try not to include yet more Apple-bashing every week, but — oh Tim! – they make it really hard for me. Take the announcement this week it would finally (I'm using that word a lot this week) open up the NFC features on iPhones to third parties globally, allowing them to create payment systems which don't have to go via Apple Pay. Yay! Except… “to incorporate this new solution in their iPhone apps, developers will need to enter into a commercial agreement with Apple, request the NFC and SE entitlement, and pay the associated fees”. What fees? Who knows — Apple isn't saying yet — but the idea that a developer can do anything at all on the iPhone without paying the company even more money seems to be one that Tim and the boys can't accept.

5. Double Cory

Another thing I try not to do is link to the same person in a week, but in addition to a great speech at Defcon, Cory Doctorow gave Apple a well-deserved kicking over everything that I seem to write about every week. And it relates back to the sad story of Dr Tangsuan, too. As Cory puts it: “Apple doesn't oppose regulation; Apple loves regulation, so long as they're the ones doing the regulating. They want to be able to shape and define the digital market, backed by the power of the state, but without any input from the state. In modern corporate orthodoxy, the state is an enforcer for corporate will.”

6. Who controls what you see on the web?

Another of Cory's concepts that I like is the idea of a web browser as user agent. It's a piece of software designed to show you the web in the way you want: with or without ads, text-only with all the crap giant images stripped out, or whatever. I was thinking about this when I read Nick Heer's article on the way Google is taking increasing control over the way that search results are represented on its site. As I have written before, the AI answers which are now infesting results are not only hard for publisher will become the default click for most users — even if they are generally pretty bad results. Currently there are many ways to get rid of them, but I doubt those will last if Google gets its way.

7. Damn, I want one

Ars Technica has a long (of course) review of the latest Framework laptop, and it makes me want one. I'm 99% sure that my next computer will be a Framework because I adore the concept of being able to easily upgrade everything on it (and reuse parts elsewhere). One impressive thing about the new model: compared to the original, you're getting roughly double the battery life. It's still not MacBook Air level, but it's close enough for most people.

8. The early history of CP/M

Annoyingly I didn't note down where I found this (if it's your site, please let me know) but this is an amazing article by Gary Kildall, who wrote CP/M, on its early history, from a 1980 edition of Dr Dobbs.

9. The later years of Douglas Adams

Although Douglas Adams was MacUser's first inside-back cover columnist (and owner of the first Mac in the UK), and Michael Bywater was a regular columnist later on, I never realised the two were friends. Or, in fact, that Bywater was Adams' occasional ghostwriter when Douglas was finding it difficult to get motivated. Parts of this article reference events I remember, particularly the launch of Starship Titanic, but there is a lot in it that I didn't know.

10. The NSA is refusing to release a historic video of Grace Hopper

Via Bruce Schneier, the NSA has discovered in its archives a video of a talk by Grace Hopper on “Future Possibilities: Data, Hardware, Software, and People” — but, so far, is refusing to release it. The reason is that the recording is in a tape format which they can't easily watch as they no longer have a player capable of working with it. That in turn means that the NSA can't view it and redact it (as, legally, they probably have to if it's an internal document). Of course, they could borrow such a player from someone else, which the NSA seems reluctant to do. This kind of information archaeology always reminds me of Mark Pilgrim's post from (crikey) 18 years ago: “I’m creating things now that I want to be able to read, hear, watch, search, and filter 50 years from now. Despite all their emphasis on content creators, Apple has made it clear that they do not share this goal. Openness is not a cargo cult. Some get it, some don’t. Apple doesn’t.”

Ten Blue links, "so much Apple, so little time" edition

1. IBM 1956 = Google 2024 (and Apple, and Microsoft, and and and)

As I've noted before, you are likely to read an awful lot of bad punditry about Apple's cases with the EC/DOJ in the next few months/years. But you're likely to hear a lot of even worse punditry about the judgement in Google's case. One thing to bear in mind whenever you read something is this: what is legally permissible when you're a smaller company can become illegal action when you're a monopoly. A “distribution agreement” that's OK when you're a scrappy upstart in a competitive market is likely to be exclusionary practice for a monopoly.

2. "The Purpose of antitrust is to protect competition"

Another great piece in The Verge was the long interview with Jonathan Kanter, assistant attorney general for antitrust at the DOJ. It's worth a read in its entirety, but probably the most important point is where Kanter talks about "the restoration and validation of a core of element of antitrust — the purpose of antitrust is to protect competition and the competitive process." This is bringing the US view of antitrust both back to its pre-1980s roots and closer to that of the EU (which is obsessed with protecting competitive markets), and it bodes badly for big tech companies.

3. Acquisition by stealth

Interestingly, one of the questions that Kanter is asked but doesn't really answer is about Microsoft's deal which saw it gain 51% of OpenAI and a chunk of control over it without actually buying the company. These "acquisitions by stealth" are increasingly common, as big tech firms see them — wrongly — as a way of avoiding antitrust trouble. The latest such deal has seen Google “buy” Character.ai by hiring its team, licensing the tech and handing investors a cheque for $2.5bn. The company still exists — in theory — but as Ed Zitron points out "without exclusive access to their models, and without an engineering team, the company is effectively dead." The problem for the likes of Google, as Kanter makes clear in his Verge interview, is that the DOJ is wise to the move. I wonder which big tech company will get hauled through court over this practice first.

4. Apple's increasingly Vista-like prompts

Since macOS Catalina, Apple has loved prodding you to check if you really wanted to do something. This is not a bad thing: Unix-based/like systems like macOS let users do many things which could endanger the security of the computer, and there are many people out there who make a living from fooling you into doing something you shouldn't. But, as Jason Snell notes, macOS Sequoia takes this a step further by making you confirm permissions over and over again — in some cases, every week. Jason says, "at some point, the user must be in charge" and this is an argument that I come back to a lot. There is a group of (very loud on the internet) people who want Apple to oversee their computers, “protecting” them from everything so they never have to learn to take any responsibility for themselves. I'm not one of those people, and I genuinely think most computer users don't fall into that camp either.

5. Weaponised litigation

Elon Musk is suing an advertising group because no one wants to put ads next to homophobic, transphobic, racist and far-right content. Nothing says “loser” like this level of entitlement.

6. Fees fees and more fees

Does Apple really think that crap like this is going to fly? As Benjamin Mayo points out, this means that, in theory, Apple could end up being entitled to fees from a service which is purchased on Android. John Gruber is correct, in saying "what Apple wants is to continue making bank from every purchase on digital goods from an iOS app". But Apple just isn't going to get that unless it starts playing the game with a little more wisdom and stops this kind of playground nonsense. Microsoft tried the same. How did that work out for them?

7. But you know Apple earns its App Store money

There is currently a deluge of fake reviews for Mac App Store products. Maybe Apple is too busy attempting to weasel out of its legal responsibilities to proactively stop them?

8. On notarisation

If you want to know a huge amount about the way that notarisation of applications works on the Mac, by the way, Howard is your man.

9. When Apple's line was a mess

Oh the Performa line. A bit before Apple was in its “beleaguered” phase, it came up with the Performa brand for its “consumer” PCs. Performas weren't actually much different to the rest of the line, but they came with some consumer software. Occasionally Mac models got three versions, all identical apart from the badge. My second Mac, for example, was the LC475, which was called that name when sold to education, but was also the Performa 475 when sold to consumers, and the Quadra 605 when sold to business. What a mess that whole era was.

10. And speaking of retro

Ten Blue Links, "Sunday is the new Friday" edition

Yeah, this one is late. I'm doing some extra work, OK? Anyway, onward.

1. Nerdy. Very nerdy

First something nerdy. Very nerdy. Of course, it’s from Howard Oakley, which is both the man who knows more about the Mac than anyone outside Cupertino and one of the world’s leading experts on cold weather survival and injury. Anyway, yes: ResEdit. If you’re old enough to remember the classic Mac, you’ll probably remember ResEdit, which let you tinker with all kinds of fun things from icons to menus. I miss ResEdit.

2. No, it’s not the fault of the EU that Microsoft hasn’t secured its kernel

Thank $DEITY$ for Paul Thurrott, who did what hundreds of other journalists couldn’t do and actually found what Microsoft was referring to when it claimed it had been forced by the European Commission to open up its kernel to third parties. This obvious bunk was swallowed and regurgitatd by the usual crowd of pundits who don’t believe big tech companies can be regulated, as well as a few who should have known better, but Paul did the work – and of course it turns out the EC did nothing of the sort. As Paul notes: “The EU didn’t force Microsoft to change Windows. It asked Microsoft to address the complaints it had raised, and this was only one of them. This change to Kernel Patch Protection was of Microsoft’s design…”

3. VCs are immoral, part 378

In particular, the odious duo of Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, who are basically backing Donald Trump so they can pay less tax – and screw everyone who will suffer, and screw America sliding into a dictatorship. It’s great to see sites like The Verge giving them the kicking they deserve.

4. Unpersons

This is your obligatory regular missive on the general brilliance of Cory Doctorow, and this week it’s all about what happens when big tech companies pull the rug out from your lives. In this case, it’s Google, but it could equally be Microsoft, or Apple.

5. Ritual de lo Habitual

I’m a little bit astounded that Jane’s Addiction’s fantastic Ritual de lo Habitual is THIRTY FOUR YEARS OLD. This interview with Casey Niccoli, who made the artwork for the cover (and without whom JA wouldn’t have been JA) brought a lot of that era back. Also Perry Farrell is clearly an ass.

6. And speaking of asses

7. And speaking of Nazis

This is a wonderful essay-length piece reflecting on the author’s family and their ties to Nazism, about which they were not even vaguely ashamed or repentant.

8. And speaking of Nazi sea-monkeys

No really. Like lots of British kids who read American comics, I was obsessed with Sea-Monkeys, not realising of course they were just shrimp. What I didn’t know what that their inventor was a Nazi who once said “Hitler wasn’t a bad guy, he just received bad press.”

9. Surprise and delight

One of the things I have been pondering of late the sorry state of user interfaces. There seems to be remarkably little thinking going on in artistic terms. This video of Susan Kare demonstrating original Mac user interface really got me thinking about it, because the Mac user interface was packed full of delightful little elements. I wonder why we don’t often see that now?

10. Of course they are doing this. Of course they are

I’m shocked, shocked I tell you that Anthropic, yet another AI start-up, are scraping data and completely ignoring robots.txt files in order to do it. Now, I am not a copyright absolutist, but one thing that a couple of decades of publishing has taught me is there’s no blanket right to suck all the data on the internet into a vast machine while offering nothing in return.

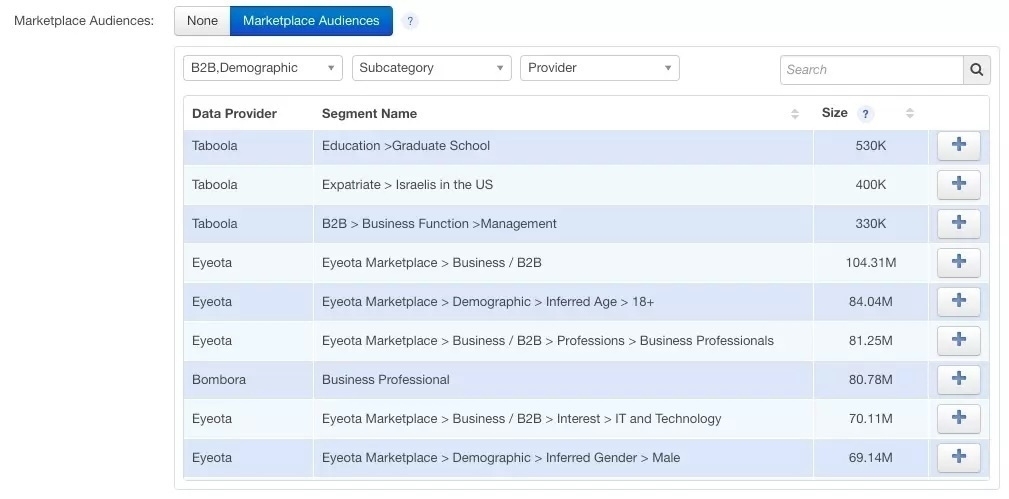

Taboola targeting

Regarding Taboola’s partnership with Apple: I’ve seen people claim that this is somehow hypocritical from a privacy perspective, assuming that Taboola’s somewhat obnoxious, clickbait-style ads must invasively target user profiles and browsing histories.They don’t. They are targeted entirely contextually. That’s the point.

This is absolutely, 100% wrong. Taboola doesn't just target on context – ie based on the topic of the page a user is looking at.

Taboola's not hiding this – in fact it's one of their selling points. They call this feature "Marketplace Audiences" and it allows you to target by a whole range of demographic and intent-based audience factors, using both Taboola first-party and third party data.

You can see this in Taboola's Marketplace Audiences dashboard:

If you think it's basing membership of an audience of "Israelis in the US" or "Education: Graduate school" just on the context of the page, I have a bridge to sell to you.

So why has Eric got this wrong? I suspect because he has a little bit of an agenda. Take a look at the last sentence in his post:

Want brash, garish advertising plastered all over the web? Reject ads personalization. Want relevant, informed advertising? Embrace ads personalization.

I have absolutely no idea why a venture capitalist who "invests in the future of mobile" would want to promote the idea that only personlised ads, which require extensive profiling, tracking and targeting, are the only way to get "quality" advertising. Maybe someone out there can help me out with this?

(Via Daring Fireball)

Ten Blue (Screen of Death) Links, "Why is my PC not working?" edition

1. Oh come on, Apple

Back when Apple changed its app guidelines to permit emulators and HTML 5-based mini games it looked like the dawning of just a little bit of light in Cupertino. Completely coincidentally these changes were made just before the DOJ case at which this kind of restriction was central. And weirdly, it looks like Apple is now walking those changes back -- without, of course, putting that in writing.

When Sticky was rejected on the basis of Rule 4.7, the company appealed. Cue a call with someone from Apple:

"In our case, after the appeal, we were called up by someone from Apple who started the call saying they did not consent to it being recorded (how’s that for inspiring trust?), who walked-back what they had said about HTML5 (and of course they did not put that in writing in the message they sent afterwards), but then came up with a couple of brand-new reasons for keeping our update off the store: claiming that we had changed the app concept… because our app was different some 4 years ago and hundreds of updates ago when it started! And including mentioning rule 4.7 regarding emulators… which we are not and do not claim to be!"

2. It's all about the user experience

Unless you have an ad blocker in place you will be very familiar with the contextual advertising from Taboola. Those blocks at the bottom of web pages listing amazing hair loss treatments and cheap junk? That's Taboola. Now you can argue that those ads are junk because people click on them (and there's something to that), but junk they are.

They do, though, make publishers a lot of money -- and now Apple wants a chunk of that money, and has struck a deal with Taboola to become an advertising partner on Apple News. Om Malik has had enough. I'm not one to pull the "this would never have happened in Steve's day" card, but really, Jobs had taste: there's zero chance he would have got into bed with Taboola for a few billion dollars.

3. The objects of our life

And if you don't believe, that, I recommend watching the video that's just been found and released by the Steve Jobs Archive. It's Steve’s talk at the 1983 International Design Conference in Aspen, and it's a great watch. For all his faults, the man had taste.

4. Eazel come, Eazel go

There was a point towards the end of the 90s when I began to believe that desktop Linux really was the future. Yes, I know. But one of the things which persuaded me was Eazel, a startup which included legendary Apple people like Andy Hertzfeld, Mick Boich and Susan Kare, who were aiming to create a user interface for Linux which did not suck. Eazel didn't last, but its product did: if you use GNOME today, you're looking at something which started life as Eazel's Nautilus file manager. I very much wish it still had Susan's icons in it. Apple rehired a bunch of Eazel employees, so if you're using macOS, you are also seeing something with Eazel DNA.

5. Return to office is a failure

Of course, it depends on what kind of work you do, but for millions of office workers around the world the one good outcome of the pandemic has been more working from home. Home working has many advantages, particularly for mid-career workers (less so for younger ones) but finally Gartner has come out and done some really interesting and in-depth research. High performing employees, in particular, hate return to office mandates because they prize flexibility and see them as a sign of distrust by managers. I've said it before and I'll say it again: if you can't manage remote workers, that's your problem not theirs.

6. Google is mind-bogglingly bad

So says Om, and I have to agree: in terms of product design, Google has got a lot worse over the last few years.

7. "Privacy preserving" Lololollol

There's a bit of a brouhaha because both Firefox and Safari have added a default-on "privacy preserving ad tracking" feature, which anonymously measures ad clicks at the browser level and passes that on to advertising companies. It's not a big deal for me -- I block ads at the DNS level, so don't see them to click on them -- but it's made a lot of people unhappy.

8. Calling for civil war is, apparently "controversial"

And now for some awful people. I had never heard of this guy before he started shooting his mouth off, but apparently he's some kind of crypto big cheese, which already tells me a lot. But what made me laugh is the headline, which refers to his comments as "controversial". Apparently, calling for civil war, calling for anyone not voting for Trump to "die in a fire", alluding positively to a conspiracy theory that the guy who shot Trump was related to Elizabeth Warren… these things are all "controversial". Not "violent", "traitorous", "racist"… oh no, those words are going too far!

9. This is where it was always going

Elon Musk has decided that he owns Twitter, so he can use it for whatever he wants. An object lesson why platforms should not be owned by billionaires.

10. Return of the underdogs

One thing Apple does extremely well is advertising, and my favourite ads of the last few years have been the ones that focus on The Underdogs - I find them incredibly funny and charming, and a bit of light relief from all the travails of tech. Enjoy.

I wouldn’t say that Apple using Taboola is going to make me rethink my Apple usage, but it’s definitely an indication that “we focus on user experience” now very much takes a back seat to “we would like to make more money” om.co/2024/07/1…

Block, block and block again

There’s a kind of person who is the reason that blocks and bans exist. They’re also the ones who argue loudest that blocking is evil, and you’ll be stuck in a filter bubble or an echo chamber if you deprive yourself of their sparkling wit. You should block these guys faster than anyone.

I recently had an encounter with one of these guys – and they are always guys – myself. They see you blocking them as some kind of cowardice, and they see tools which let you control your own information environment (filters) as a refusal to engage with whatever views they believe to be correct and important.

Bluesky's moderation service is optional – you can turn it off, and be exposed all the hate speech you want. But people like Dorsey and my random guy don't want you to be able to block or filter views you disagree with. What they want is a form of coercive control, the ability to override what you desire to make it what they think is good for you. Think Elon Musk, putting himself into every single timeline and proposing to make people (i.e. him) unblockable.

Filtering is another kind of user agent, a representation of my control over what I want to see and do online, and that's a good thing. Similarly, genuinely federated services like Mastodon (but not Bluesky, yet) allow you to devolve moderation to a trusted administrator (for your instance) and add your own personal blocks and filters too. In this way, Mastodon allows the creation of genuine communities, which share values and also decide to what degree they want to connect to the rest of the world. They can be as isolated or federated as they wish.

Ten Blue Links, "Three Lions On My Shirt" edition

1. Couldn’t happen to a nicer billionaire

What’s interesting about the European Commission’s charges against Twitter (which I refuse to call X because it’s a stupid name) is the focus on the blue checks' policy. Everyone knew this was a bad idea driven solely by Musk’s hatred of anyone more fascinating than him. The chickens have well and truly come home to roost – at a cost of up to 6% of the company’s global revenue.

2. The end of the cheap money era

If you’re a football fan, you might know the name Clearlake Capital for its ownership of Chelsea – and the fact that it’s spent getting on for £1bn on players. All that money has to come from somewhere and like all private equity companies, Clearlake has piled a lot of debt on to its companies. The era of cheap money is over, so it’s finding it harder to follow the same model.

3. The toxic nature of the OpenAI board seat

Not that long ago, Microsoft was proudly talking about its “observer” seat on the OpenAI board. Now it’s decided it’s “no longer necessary”. I’m sure it’s a complete coincidence that both the EU and US authorities have been looking at the relationship between the two companies with interest. The tech pundits will be along to tell us how this is stifling innovation or some such real soon now.

4. And speaking of private equity

Charlie Mullins, who sold Pimlico Plumbers to a private equity company, now has regrets. I’m not surprised: the private equity model is based on “efficiencies”, which can be translated as “worse services”, and Pimlico became successful because of its customer service. Of course, it doesn’t matter to the PE companies: they can always flip the business to some other sucker further down the line, after they have drained it through special dividends.

5. Little tech (not to be confused with small tech)

Techno-optimism is so last week. Now, the odious Andreessen is promoting the idea of “little tech” which, of course, means the kind of startups that A16Z invests in. And of course, there’s no need for those companies to actually grow: the aim is to flip them to one of the big tech firms before the need to make a profit actually arrives. I’m actually glad that the thing which some smart analysts once told me didn’t happen – VC companies investing in businesses solely to flip them – is now a part of the business they’re happy to admit is the goal.

6. AI slop

Christina Warren noticed something odd: her byline was appearing against articles which she hadn’t written. It turns out that TUAW, which she used to write for a good decade and a bit ago, had been acquired by the kind of company which churns out AI-generated crap content, and they had been using the bylines of people who used to work there. Related: I have no idea who owns some of the domains I used to work on, including macuser.co.uk, which doesn’t appear to have moved to Future alongside the old print product.

7. Piracy is back, baby

Wendy Grossman – who has been writing a weekly column on the internet for longer than some of you have been alive – has written an excellent piece on the second coming of internet piracy. As Wendy notes, the emergence of piracy as a more mainstream activity comes at the same moment that streaming services have started to get pricier and worse. The removal of decades of Comedy Central clips is teaching a new generation that you can’t trust content will remain online. There is a reason I have a couple of 4Tb drives attached to a local machine, kids.

8. RIP Bruce

I missed that Bruce Bastien had died. Before Microsoft used tying, bundling and other illegal behaviour to destroy all its competitors in the 1990s, I used WordPerfect rather than Word, and it still offers features which you can’t get anywhere else. Technically, it still exists, but I wouldn’t recommend it. Related: I’m amazed to find you can still buy Quattro Pro too.

9. Switching

You can now easily transfer your images from iCloud to Google Photos. Why would you want to do that? Because if you have many images stored only in Apple’s cloud, downloading them all and then exporting using the Photos app is a horrible experience. Unless you like watching Photos’ memory usage balloon to more than 64Gb and then take down your whole system, of course. Google Photos, on the other hand, lets you download them all from the browser thanks to Google Takeout.

10. No politics allowed

When big tech platforms talk about not allowing political speech, what they almost always mean is “no political speech we don’t like”. And when Meta says it about Threads, what it means is “no marginalised people here, please.” Kudos to MacStories for publishing this.

Ten Blue Links, "delayed by the election" edition

1. I'm shocked, shocked I tell you

Surprise! The use of energy-intensive AI to make stupid graphics that look instantly like AI and write words that it would take you five minutes to right have pushed Microsoft's greenhouse gas emissions up by 30% since 2020 and Google's up 48% since 2019. But it's OK, Google's energy usage is only 0.1% of the entire planet's, it's not like it's much… there's more on this in Paris Marx's article, which is a good read too.

2. Destructive investment

Related to this of course is the entire system of investment, which focuses — at least in the US — on the primacy of shareholder interests over those of the country. This system has led directly to a lot of terrible outcomes, from Apple's “growth at all costs” approach to abusing its power in the market through to, well, Elon Musk. The same dynamic is gradually seeing many of our most valuable institutions fall into the hands of private equity companies, a group for whom the phrase “vulture capitalism” was virtually invented. And much of this delusional behaviour is, unfortunately, driven by myths about early tech companies, from the startup-in-garage to the founders-as-heroes. I have to confess that I, too, once believed in these myths. I no longer do.

3. When Apple says protecting users, it means protecting profits

A single app store and an operating system which doesn't let you install the apps you choose is a single point for any government to control your experience. That's one of the reasons why battles to prevent Apple and others having a monopoly on software installation is important. Apple's desire to “own” software distribution is not about protecting users: it's about protecting profits. Case in point: the company has bowed to pressure from the Russian government and removed a number of VPNs, which allow Russians to bypass state censorship, from the App Store. If Apple allowed sideloading, which it easily could, this would not be a big deal. But it would rather adopt the “principle” that users aren't allowed to install software from anywhere they want rather than oppose state surveillance.

4.Apple “crippled watchOS to lock out competitors”

When Apple changed its heart monitoring APIs in watchOS 5, it's claimed, it did so to ensure third-party competitors didn't get access to the same data its own apps had. I don't know if this is true, but even if it's not, it's another example of why platform owners like Apple need to be made to ensure a level playing field if innovation is to thrive.

5.Apple (Computer) Says no

Want to run DOS on your iPhone or iPad? Apple says you can't. Why not? Because Apple says so. Just because you paid Apple £1000 for your iPhone doesn't mean you get to install things you want. It's not like you own it or anything. What makes this even worse is that notarisation should be a system which is used solely to stop malware. In practice, Apple is simply using it to enforce its app store rules outside the app store — which discredits the whole purpose of notarisation.

6.Nerd History heaven

How well I remember the process of juggling INITs and CDEVs. As always, Howard has the details.

7. Meanwhile, In Microsoft land

Now if you're thinking about maybe ditching your Apple products and exchanging them for one of those fancy new Copilot + PCs, you might want to reconsider. Microsoft is going through one of its periodic seasons of hand-wringing about security, while, of course, adding in insecure features by design. Everything that Microsoft is currently doing to Windows is aiming towards a single goal: to make sure you can't use Windows without connecting to a Microsoft account, and ensuring it has access to your data. Case in point: the New Outlook, which the company has been prodding users towards for a while. Unlike the old bundled Mail app, which used IMAP or POP, new Outlook only talks to Microsoft's servers: to use it with a non-Microsoft account you have to give Microsoft access to all your third-party email. Oh, and don't think you can use it without also having Edge installed. Not doubt, if questioned, it would claim this is all for “security” or “the benefit of users”. A plague on all their houses.

8.Proton Changes

Proton, everyone's favourite bunch of Swiss-based nerds, is going to move towards a non-profit structure. This is a good thing. Owned by a Swiss non-profit foundation, the company can't be as easily taken over — and the foundation itself is legally obligated to act in a way which supports its original mission.

9. Docs, docs and more docs

And speaking of Proton, they launched their own collaborative cloud-based document system. It seems like a pretty private system: everything is encrypted end-to-end, and no data is collected that isn't necessary to make the thing work.

10.Sixteen Kids and a hitman

Away from the world of technology for the last couple of pieces. This story of an evangelical man who went on to the dark net to hire a hitman to have the biological parents of his adopted children murdered is quite the thing.

Ten Blue Links, Infamy, infamy, they’ve all got it infamy edition

1. Oh Perplexity, why must you test me so?

I have been a big proponent of Perplexity for a while, mostly because I found it incredibly useful as a research tool. Turns out the reason it was useful as a research tool was it was scraping a load of data that it shouldn’t, pretending to be academic researchers to get access to Twitter, and more. Suffice to say, I no longer recommend it. But more than that: organisations which engage in this kind of perfidious conduct should be actively shunned.

2. The cows are lying down

And speaking of AI, 404 Media decided to conduct an experiment: how much would it cost to basically clone their site using LLMs and off-the shelf tools? The answer: $365.63. And they wouldn’t have to employ any of those pesky journalists to do it.

3. Better by you…

What was the internet like 20 years ago? Without coming across like an old git, the answer is just “better”. Like Richard, I started blogging using Radio Userland, a long-forgotten application developed by Dave Winer. Like everything Winer makes, it was really an outliner (when I first worked at Apple in 1989, we used MORE for presentations – it was also a Winer product, and also really an outliner). It was also local: it generated all the HTML for your blog on your Mac and then uploaded the changed files. I still there there’s something in that approach.

4. Are you though? Are you really?

Ever wondered what it’s like being a low-ranking professional tennis player? No, I hadn’t either — but this great piece in The Guardian had me laughing, then shaking my head, then laughing again. My favourite line: ““I am going to fight my natural hand-to-eye coordination, no matter how bad it is, I am going to hit all of these motherfucking balls until I develop a shot. I am going to do this for months and months and months: I am not going to let these rich fucks beat me.”

5. Breakin’ the law, breakin’ the law

Confession time: whenever I buy an ebook which is encumbered with DRM, I crack it and save a local copy. I don’t give it away, loan it, upload it anywhere — but I don’t trust companies to keep their unspoken promise that I will always be able to access that book. Why don’t I trust them to? Here’s why. And yes, I did have books which used this DRM system.

6. And speaking of Microsoft DRM systems

Oops. Repeat after me: DRM is pointless.

7. Creative destruction

Look, in the great long list of terrible things that the Tories have spent fourteen years doing to Britain, the effective destruction of much of the support for the arts that had been built up for decades may not seem like the worst. But in terms of the breadth of people it affects, it’s probably the broadest. Obviously, underfunding organisations and forcing them to spend more time chasing money than supporting creative work is bad. But they have also hammered funding for adult education cources which aren’t “vocational”, which means that drawing, painting and other creative practice classes are not being cut – something disproportionately affects older people. Capitalism hates creativity.

8. PRs: please don’t do this

I don’t get that many unsolicited press releases these days (don’t think of this as a request) and I doubt that even during the Journalism Peak of my career I got as many as Jay Rayner, but I completely sympathise with his public letter asking that PRs do at least the minimum amount of research before sending him stuff.

9. The grumpiest man from Wales is back

God I love John Cale. Way back in the first years of this century I was lucky enough to see him do readings from his book What’s Welsh for Zen? at Komedia in Brighton, and he almost bit the head off an audience member who was trying to video him. In the twenty four years since he’s just got grumpier and he remains a vital creative force. I adore him.

10. The best reason not to use AI

We really do not need another global power crisis while we’re trying to stop the planet burning.

Microsoft 1998 = Apple 2024

My read on this is that the EC’s stance is that its designated gatekeeping companies — all of which happen, by sheer coincidence I’m repeatedly told, to be from the US or Asia — should be forbidden from evolving their platforms to stay on top. That churn should be mandated by law.

Those of us old enough to remember back to the 1990s will recall Microsoft making very similar arguments about how antitrust was going to stifle innovation:

The Microsoft Corporation said today that a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Justice Department and several State Attorneys General is without merit and will hurt consumers and the American software industry, a leading contributor to the U.S. economy. Microsoft said it will vigorously defend the freedom of every American company to innovate and improve its products, a principle that lies at the heart of this case. Microsoft said today’s action by the Government will set a harmful precedent in which government intervention into a healthy, competitive and innovative industry will adversely impact consumers and a U.S. company’s ability to improve its products. The company said it appears that the lawsuit is more in the interest of a single Microsoft competitor than in the interest of American consumers.

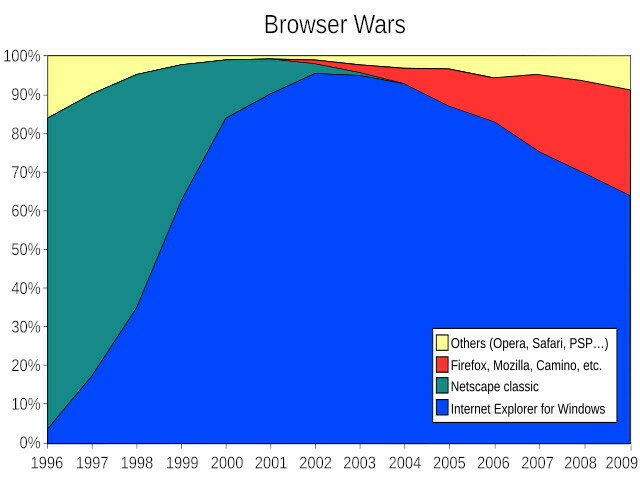

Oddly enough, when Microsoft lost its cases' innovation didn't end. What did decline after the settlement of the DOJ and EU trials was Microsoft's browser market share -- a fact which some commentators would have you believe is a complete coincidence and nothing whatever to do with governments forcing Microsoft to stop being an abusive monopolist.

Apple delays AI in the EU. Maybe.

Another day, another spat between Apple and the EU.

I'm not going to focus on the ridiculous idea that the DMA Is too vague, or that someone EU law is about "the spirit of the law" rather than its letter. You have to know nothing about EU law – or, in fact, how any law works – to believe that. Neither am I going to address the nonsensical thought that the EU is making design decisions: if you believe that regulation is "making design decisions" then both Washington and Brussels have been making design decisions in the car industry for decades.

Nor am I going to say much about the hysterical "EU IS BEING JUDGE JURY AND EXECUTIONER!!!" piffle. Just go read Article 45 of the DMA. It won't take you long, and you can read it in many languages.

What I will say, though, is that the idea that companies can't know if a feature is compliant before they release it – an idea that's well-beloved of quite a few pundits – is at best ignorant and at worst downright deception. Article 8(3) of the DMA lays out how companies can engage with the Commission to "determine whether the measures that that gatekeeper intends to implement or has implemented to ensure compliance with Articles 6 and 7 are effective in achieving the objective of the relevant obligation in the specific circumstances of the gatekeeper."

In other words, companies can engage with the EU before something is released to work out ways to stay within the DMA. The idea that it's just a crap shoot and WHO KNOWS WHAT THOSE CRAZY EUROS WILL WANT is just silly.

And maybe, in fact, that's what Apple is doing behind the scenes – in which case, it should just cut the crap and say it. Part of the mystery about this is we actually already knew some of it. Apple had already announced it wouldn't be released Apple Intelligence except in US English before the end of the year. That means, of course, EU countries weren't going to get it for a while anyway.

In the non-explanation explanation which Apple provider to John Gruber, it said this:

Specifically, we are concerned that the interoperability requirements of the DMA could force us to compromise the integrity of our products in ways that risk user privacy and data security. We are committed to collaborating with the European Commission in an attempt to find a solution that would enable us to deliver these features to our EU customers without compromising their safety.

This of course explains nothing, except stringing together “concern” with “privacy”, making ti sound like the big bad EU is going to force Apple to compromise the privacy of its users. Given the EU's long history of protecting the privacy of its citizens from US tech companies determined to operate in a wild west of personal data, this seems unlikely. And given Apple's own track record of ensuring users can't withhold their own data from Apple when it's beneficial to the company, I know who is on the side of user privacy here.

Apple is happy to cave in to even the most repressive regimes and forget about user privacy when it's beneficial to its bottom line. On the other hand, when user privacy conflicts with Apple's profits, it will go to the mat to defend its right to do what the hell it wants. That's why even if you tick the box marked "disable sharing of analytics", your iPhone will continue sharing analytics with Apple.

I really don't understand what Apple's game is here. Getting into a pissing match with a multinational block that sees the sanctity of free markets as its reason for existence and markets locked down by companies as an existential threat is not going to end well for any company.

Does it think it's going to get the DMA overturned? That a bit of magic PR will encourage a consumer rebellion of iPhone lovers riding to its rescue? I suspect it is still labouring under the impression that it's still considered “the misfits, the crazy ones”, the people who are on the side of consumers. A brand so beloved that even the EU can't touch it.

If so, I think it's become disconnected from reality. We saw with the controversy over the "crush" ad that people are now less likely to give it the benefit of the doubt, less likely to see it as the plucky underdog on the side of creative people.

For all its focus on privacy – and its genuine victories – Apple is no longer trusted in the way it was. It's begun to be considered just another big tech company, one that's prepared to throw its toys out of the pram if it doesn't get its way. When a company's value is in the trillions, it's very hard to credibly say you're on the side of ordinary people.

Ten Blue Links “Liberation Serif is cool now” edition

1. Dell to employees: “screw you”. Employees to Dell: “you first”

Everyone enjoys seeing a few chickens coming home to roost, and especially when the chickens are landing on the roof of a huge corporate entity and crapping all over its well-manicured rooftop executive garden. The latest to find out the hard way is Dell, which ordered its employees to make a choice: become “hybrid” workers travelling to an office 39 times a year (monitored of course) to spend their time on Zoom calls from an empty office, or be “remote” workers. Oh, and if you’re remote, you’re not allowed to get promoted or apply for another role in the company, ever.

No doubt the conversation in the executive suite was about how remote workers weren’t “team players” and so weren’t the kind of people who “deserved” promotion, no matter how well they actually do their job. But it’s turned out that if you choose to wield the stick rather than the carrot, people don’t respond too well: in fact, nearly 50% of employees have chosen collectively to shrug their shoulders and stay at home.

That’s bad enough now, but it’s also really going to choke Dell as a business in the future. Retention is always an issue, and the retention of employees who have no prospects in a company is an almost impossible task. Any competent leader at Dell will be spending a lot of their time in the next year recruiting, while good employees go elsewhere to further their career in remote roles.

And failing to retain costs money: way back in my early career, a slightly drunk finance director told me that when you accounted for the time of managers recruiting, the effort to find someone good, and short-term costs of backfilling vacant roles, you were basically burning about £2000 every time you recruited a replacement. The cost to Dell of increasing employee churn, with around 120,000 employees, is a lot: if this move adds another 5% to its churn rate, it runs into hundreds of millions of dollars.

And for what? Because Michael Dell likes to see a “lively” office? Michael, the 1990s called, and they would like their ideas about business back.

2. It was 20 years ago today…

How can it be 20 years since Cory Doctorow travelled from London to Redmond and into the belly of the beast to deliver the good news that DRM doesn’t work? Cory was right: DRM doesn’t work, and it never has. But the tech companies have managed to use its spiritual successors likes parts pairing and app stores, enabled by exploiting the intersection between bad law and technology, to do things which would have sounded wild to them in 2004. Had Bill Gates thought about a software store on Windows that he got 30% of the cut from for no additional work, he would have probably drooled so much the hydration would have killed him.

3. And the bullshit machine goes marching on

I have to confess that I was pretty enthusiastic about Perplexity, which I’ve used as an example of how a large language model-based tool could actually improve on the existing state of the art. And I still believe that search, in the way we think of it now, is going away and will be replaced by conversational engines giving answers that tap into public data. You shouldn’t have to master how to use a search engine (or the frankly shitty experience that most SEO-led pages now deliver) to find what you want. And where you don’t quite know exactly what you want – such as when you’re buying a product – having a conversation with something that knows about products is a better way to do it.

But oh: it turns out that Perplexity not only just makes stuff up, it has been scraping data it shouldn’t have and trying to cover its tracks. Why are startup people, so often, utter shitheads about stuff like this? It’s just so unnecessary.

4. $325m worth of humans delivering pizza

I absolutely love Joan Westenberg’s writing, and this piece on Zume is a perfect example of how she cuts through the bullshit. Zume, in case you missed their flashy pitch, was going to revolutionise food delivery by cooking the food in ovens on route to you. It started with pizza, but, of course, had the stink of “disruption” about it, the kind of smell that always ends up spreading to a thousand other areas. It turned out, of course, that its magic robot roving ovens made pizza that was just bad – so they ended up having stationary “mobile” ovens and using human delivery drivers to actually take the product to the customer.

In other words, VC’s decided that a company of pizza vans was worth $2.25 billion.

Masters of the universe, my ass.

5. Here we go again

Governments really, really, really hate encrypted messaging. The “good” governments hate it because they think it aids criminals; the bad ones hate it because it aids dissidents. And just because we beat them once, doesn’t mean they’re not going to try it again. Meanwhile, you can find me on Signal.

6. But muh users!

I see that Apple is up to its bullshit again? A terrible shame that it’s not going to get its way.

7. AI is a feature, not a platform, not a product

I’ve seen a few articles floating around about how Apple’s “Apple Intelligence” announcements shows that AI is a feature, not a product or platform (Benedict Evans has written a good one) and there is definitely something to this. But it’s worth remembering that the canonical use of “feature not product” was Steve Jobs telling this to Dropbox. And somehow, Dropbox is not only still around, it’s a good product – and still better than anything Apple has developed. What Apple has done is great: but in terms of the future, general purpose intelligence will probably win out for many tasks. Just because automatic gearboxes exist doesn’t mean sometimes a manual shift isn’t the right option.

8. Developers? Before the app store? THIS CANNOT BE

Someone should tell Tim Cook that a reality distortion field only works if you have the charisma of Steve Jobs.

9. Meanwhile, in Keir Starmer’s inbox…

...will be the terrible state of the universities, several of whom are likely to go bust within the first year of a Labour administration. Lots to do, boss, lots to do.

10. Masters of the universe, Redux

Every day, there’s another piece of evidence suggesting that far from being the Übermensch of their dreams, masters of the universe, probably lords of time, venture capitalists are really quite dumb. You have to love it.

Ten blue links, "what a beautiful day, hey hey" edition

1. Looks like a publisher, is actually an AI content farm

I'm still hearing about publishers who think the answer to their prayers is replacing human writers with large language models. But the real issue, and the one that actually puts the whole publishing model at risk, is the ability of companies to just start up massive "news" websites, win for a few months before Google works out they are are crap, rinse and repeat. BNN was an example o this. I saw it a lot for a while, but then it vanished. Here's the story.

2. Publishers doing the right thing

Over here, a group of publishers are suing Google for rigging the ad market. I don't know, yet, which publishers, but my gut feeling would be it's mostly small ones as larger ones tend not to want to antagonise Google. This is of course a better approach than anything which relies on copyright, news taxes and so on, because it's simply true: Google and Facebook have, between them, stitched up the ad market.

3. Alexa, why does my toothbrush not work?

Things which rely on a connection to the internet to work are always vulnerable to simply being switched off by the people who made the product, and there's no better illustration of this than Oral-B "smart" toothbrush. Part of me thinks that if you bought a toothbrush you could talk to you take a little bit of the blame, but I have also been caught by products which promised to have functionality which later disappeared. So I can't blame you too much if you bought a toothbrush expecting to be able to, erm, use it to manage your smart home.

4. Garry Tan promotes antisemitism

You might not know about Garry Tan yet, but you're likely to hear more about him. He's one of those venture capitalist vultures who seem to believe that having a lot of money makes them smart, but of course he's as dumb as the next arrogant bozo. He's so dumb, in fact, that he has taken to promoting antisemitic conspiracy theories aimed at George Soros. Well, he's either dumb or just a racist. Which is it Garry?

5. Was Jack Dorsey always this awful? Reader, I am adding to this headline purely to avoid my own law, because yes, yes he was

Dorsey doesn't like plebs, doesn't want to take any responsibility for anything and has a shitty beard. That's all.

6. The Tories hate the young, but luckily the young hate the Tories

It's entirely predictable that the Tory manifesto will be full of regressive nonsense, but what they have managed to do in recent elections is dangle just enough carrots towards young people to make them, at least, not bother to vote Labour. Usually this involved some magic incantation involving the word "aspiration". Not so now! Showing once again that Sunak has no political instincts at all, he has instead adopted a "fuck you young people" approach which is likely to get people voting against him, while adding nothing significant to his popularity amongst older voters. Stupidity, he is it.

7. Things I did not realise about my home town

It basically was the place the modern version of Dracula first made his appearance. Go, Derby!

8. Speaking of the undead

Tim Montgomerie, editor of Conservative Home, expects to see a poll which has Reform ahead of the Tories. I wouldn't be surprised either, and it will probably mean the Tories lurch even more to the right. But: they should also remember that they are so far behind in most polls that even adding every single Reform voter to their tally would still see them lose, comfortably. And it would probably alienate what few more moderate Tories they have left.

9. Now that's the right way to do AI

10. At last

On one hand, Apple actually building a proper password management app is a good thing. The password keychain functions are a little bit buried at the moment, which discourages people from using them -- and using a password manager is a great way to Do Better Secures. But... Apple's features can be a bit of a roach motel: you can get in, but you'll never get out again. So far, that hasn't been true of passwords, but let's hope no bright spark in Cupertino thinks that now is the time.

Weeknote, Sunday 2nd June 2024

First of all, how the hell is it June already? Is it just me? Is time passing at a ludicrously fast pace?

OK, maybe it is just me.

This week was, in work terms, truncated: A bank holiday plus a day off on Thursday made the week feel even shorter than normal. Since Thursday I have been up in Suffolk for a little mini-gathering of the clan, seeing my niece, her husband, and their two lovely children – the children for the first time ever. They all live over in Adelaide, where my brother and his wife settled over thirty years ago. An outpost of the Betteridge’s, established.

Because I’m quite a bit younger than my siblings being a great-uncle has come pretty early. I’m less than 20 years older than my youngest niece, which means we share quite a few cultural references, probably more than my siblings in some ways. And my niece’s lovely husband (who once managed to absolutely charm my mother, which gives him bonus points) is a wonderful, lovely guy, too.

Spending time away from home is good, but I’m less enamoured of living out of a rucksack than perhaps I would have been twenty years ago. I love being away, but the prospect of being at home in my own bed is what makes travelling special. The journey may indeed be the reward, but being able to soak in my own bath for a couple of hours is also part of the journey, in a way.

This week I have been reading Beyond the light horizon by Ken Macleod, the third in a series which I have quite enjoyed. It’s a nice near-future romp which features submarines which are actually spaceships, a mysterious alien intelligence, and a European Union that’s developed into a more communistic union – and which works better. Thank you Ken for painting a picture of a near future that’s not totally wrecked. I enjoyed the first volume a lot, thought the second lagged a little (as second volumes often do) and am enjoying the third one a lot more so far.

This week I also bought a new iPad, the 11in iPad Pro with the spangly new M4 chip in it. As a bit of background, I actually had two iPads: an M1 12.9in, and a recent iPad mini. Since I bought the MacBook Air M2, the 12.9 – which was intended to be my travelling machine – has hardly had much use. The 11in iPad Pro is intended to replace both, and be the device I take on trips and while commuting.

This trip to Suffolk was its first journey, and it’s done really well. The new keyboard is a delight to type on. While I didn’t mind the previous Magic Keyboard, this is a far better feel and more akin to the excellent MacBook Air keyboard. It’s also – of course – a great book reader, and I have spent a lot of time reading on it. The screen is great, but honestly the screen on every iPad I have ever owned has been great. Is it noticeably better than the older iPad Pro? Not to my old eyes, but that’s because the older iPad Pros already had great screens.

More importantly battery life is good, largely (I think) thanks to the shift to OLED and the power-sipping qualities of the M4. Does it need all that power? No. Will there be applications in the future where it’s required? Almost certainly. Roll on WWDC in a few weeks.

Ten blue links, just when I thought I was out edition

There’s a lot of AI in this edition. Sorry. One day I’ll stop talking about it, probably when silenced by the machines. For those whose interests are less one dimensional, I’ve included some actual culture towards the end.